A DRAMATURGICAL TRAIN WRECK? Nope — the Dolls wag this theater piece. |

There are tears but no onions in The Onion Cellar (at Zero Arrow Theatre through January 13). But who needs emotionally catalytic root vegetables when you have the Dresden Dolls? The powerful punk cabaret duo are the reverberating center of the Günter Grass–inspired theater work that the American Repertory Theatre, under the direction of Marcus Stern, has bounced off them. Just the chance to see and hear Amanda Palmer and Brian Viglione at close range in the fabulous club carved out of Zero Arrow by set designer Christine Jones is worth clamoring for. If there is no direct evocation of The Tin Drum’s post-war Düsseldorf boîte, to which patrons repaired to cut onions and spill repressed emotions, there is a similar mix of surrealism and detail: a winsome young woman in a bear suit connects mysteriously with a bartender; a twitching lad called Onion Boy engages in furtive licking with a mate called Mute Girl. And despite some missteps, the central tale wedged in poetic fragments amid the nightclub patter does link to the Dolls’ songs, leading up to Palmer’s savage rejection of an abandoning father in “Half Jack.” Here the unresponsive dad — the Onion Cellar owner, mostly as mute as Mute Girl and deep in his cups — gets not so much an exorcism as a strange present. But this is no dramaturgical train wreck, as newspaper interviews may have led you to expect. The Dolls wag the theater piece, but at least the tale is a tail.ART approached Palmer about collaborating, and she plugged the invitation into a long-simmering desire to adapt the “In the Onion Cellar” chapter of The Tin Drum. What she had in mind involved real raw onions, real raw emotions, and Nazis. What Stern has shaped from material contributed by Palmer, writer Jonathan Marc Sherman, himself, designer Jones, consultant Anthony Martignetti, “and the cast of The Onion Cellar” is less raw than shattered and dreamy: a fable of an abandoned daughter who as a child collected tears in Mason jars and who was later killed in a car crash, having tried for years to make connection with long-gone dad. Also on tap is a continuing story told by red-clad and ruffled Remo Airaldi as the club’s MC about growing up in Peru a sensitive lad given to crying that infuriated his macho dad. For comic relief that doesn’t quite work, Karen MacDonald and Thomas Derrah turn up at the bar (there is one, as well as a punk-Weimar-clad wait staff) as a middle-aged Midwestern couple traveling the country in an RV named Harvey.

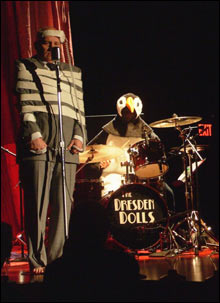

Meanwhile, the Dolls put on an electric show, drumsticks exploding from Viglione’s hands, Palmer attacking her keyboard like a pugilist as she puts an affecting strain on both her larynx and her emotions. The bristling 90-minute set includes — in addition to a slinky, Weill-like introduction to the Onion Cellar penned and sung by Palmer — Dolls signature tunes including “Necessary Evil,” “Good Day,” “Coin-Operated Boy,” “Delilah,” “Sex Changes,” and “Sing,” with Viglione letting loose at one point with a long, impossibly athletic drum solo that brings the house down. Derrah, in the guise of a disturbed man trussed up in tape, also takes the stage, turning in a rhythmic screed that falls somewhere between auctioneering and a vocal drum solo.

So what’s being attempted here? To bring the energy and the immediacy of a rock concert to a theater happening that casts the audience as itself, in a space where lighted liquor bottles float against a black background and a very theatrical band take a red stage lined with bare-bulb footlights as wisps of story ricochet amid the crowd? If so, it works to some degree. The Dolls’ loud, pounded rhythms and Palmer’s unfiltered wailing give anger and depth to material that would otherwise seem underdeveloped and personal in a manner more self-indulgent than from-the-gut. But this is a specific experiment (and a great rock show). Don’t look for productions of The Onion Cellar at your local community theater, with a high-school band standing in for the Dresden Dolls.