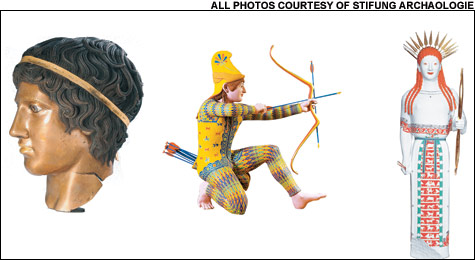

OLD PAINT: (From left) Head of Youth, Roman, early 1st century AD; Trojan Archer from Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, Greek, c. 490–480 BC; “Peplos” Kore, Greek, c. 530 BC. |

The Parthenon in Athens, Rome’s Pantheon, and the great naturalistic sculptures of ancient Greece and Rome have stood for centuries as emblems of the heights of Western culture. Even in ruins, they’ve represented pinnacles of beauty, simplicity, and humanism. Might our understanding of these familiar stone monuments not only be mistaken, but also harbor a racist legacy?When we think of the ancient Greeks and Romans, we picture them among the sober silent white stone of their surviving sculptures and columned temples. But the exhibit “Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture in Classical Antiquity,” at Harvard’s Sackler Museum, presents striking evidence that our sense of ancient sculpture is distorted because we’ve forgotten that the white marbles were once painted in bold Technicolor.

Based on two decades of detective work by German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, here some 20 plaster replicas have been painted to approximate the ancient sculptures’ original appearances. The look is disconcertingly garish. Vivid red, blue, and green scales cover a Greek warrior’s helmet. A funerary monument for another warrior depicts him in yellow-leather armor decorated with blue stars and a green and yellow lion’s head. All this color feels wrong, wrong, wrong. And it’s this visceral reaction that makes the exhibit so intriguing.

“In the study of ancient art there is scarcely any area so much shrouded in mystery as the coloring of the temples and sculptures,” Brinkmann writes in the catalogue. “Since the artistic works achieved their real and intended effect by means of coloring, this also means a serious loss in understanding of them.”

Our notion of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture seems to originate in the Renaissance. Europeans made painted sculpture up through the medieval, Romanesque, and gothic periods. But around the 15th century, as the Renaissance dawned, artists and leaders sought inspiration in ancient Greece and Rome. These civilizations were seen as heights of culture — as well as heights of power — that artists and rulers emulated. Renaissance discoveries of ancient Greek and Roman marbles with their paint worn off by centuries of exposure to the elements (and then cleaned) inspired the great unpainted marbles of artists such as Michelangelo — and centuries of sculpture that followed.

Still, it’s not exactly news that the ancients painted their sculptures. In fact, research into painted classical sculpture goes back at least 200 years. Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts even presented an exhibition on painted classical sculpture more than a century ago, in 1891. And the brilliant colors employed by ancient cultures are apparent on surviving glazed-brick-wall reliefs from ancient Babylon (in present-day Iraq) and dazzlingly ornate coffins and statues found in the tombs of ancient Egypt.

But the unpainted Renaissance sculptures, arising out of ignorance of classical polychromy, seem to be where Westerners began equating bare carved stone with ancient ideals of strength, sobriety, nobility, simplicity, purity — ideas that became bound up with Western notions of race and ethnicity, of whiteness. These ideas continue to pop up in contemporary culture, most obviously in portrayals of Romans in Hollywood epics. Roman characters have often been played by Brits with Shakespearian airs, suggesting analogies between the Roman Empire and the British colonial empire, with its Anglo dominance of Indians and Africans. By reconstructing the color of these ancient sculptures, archaeologists are also restoring some of the ethnicity that was bleached out of the originals.

“Gods in Color,” organized by Munich’s Stiftung Archaologie (Archaeology Foundation) and the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (National Antiques Collections) and Glyptothek, presents a fragment of a 6th-century-BC Greek marble Kouros (male youth) borrowed from the MFA. Red-brown paint is plainly visible on the curly hair falling down the fellow’s back. Brinkmann and his collaborators use raking light, ultraviolet light, and microscopic analysis to reveal traces of paint not apparent to the naked eye, as well as raised areas that paint protected from erosion. Ancient texts and scientific analysis identify ancient paints: mostly a mix of mineral pigments with organic binders such as egg or wax. Often only the lowest layers of paint survive. And some colors (red, blue) seem to last better than others. So the re-creations are a mix of evidence, guesswork, and approximation. “These partial reconstructions are pretty certain, but they give us a misimpression, because they only show us what has survived, not all that would have been there,” says Harvard curator Susanne Ebbinghaus, who organized the Sackler presentation with her Harvard colleague, curator Amy Brauer.

Check out an original marble head carved at Greece’s Cycladic islands in about 2550 BC that still bears faint red dots painted across its cheeks and forehead — perhaps depicting body paint or tattoos. Based on paint traces and close study of weathering patterns, a plaster copy of a similar sculpture, with strikingly simplified anatomy, is painted with blue eyes, red lips, and dots across the cheeks. The distinctively wavy blue hair, which zigzags down her back, bears a family resemblance to Greeks of today.