LOVED: Charles Simic is a poet not of big gloomy poems but of small glooms and fears that haunt our waking lives and disturb our sleep. |

After I exited Lafayette College in June 1964, I spent the summer as a cub reporter for my Connecticut home-town newspaper, The Trumbull Times. The only news worth repeating is that I interviewed Jayne Mansfield. She was doing summer stock in a nearby theater and promoting her record album Byron, Tchaikovsky and Me. The interview took place in a motel room. Ms. Mansfield sat on the bed wearing a bikini. Behind her sat her agent, the soon-to-be king of porn movies Matt Cimber. Being a wiseacre, I asked, “Miss Mansfield, what is your favorite Byron poem?” She whispered with Cimber, then turned to me and purred, “All of them are my favorite.”

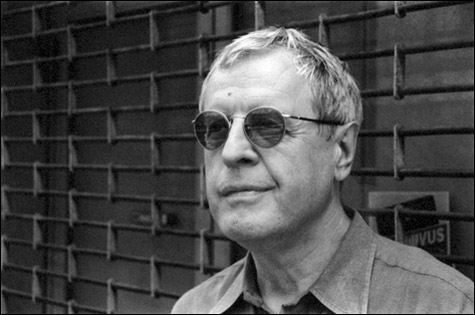

Ms. Mansfield notwithstanding, most poetry readers make their own selections of their favorite poets. Recently in an unconvincing, and in my opinion unfair, New York Review of Books review of Robert Creeley’s Collected Poems, CHARLES SIMIC bemoaned the thick “collected” volumes of the recently dead like Creeley and Kenneth Koch. Simic argued that books of selected poems would best serve most, if not all, poets. At present he is as good as his word, and the current 60 Poems (Harcourt) is the result. Well, half as good as his word, since the book selects only from 1987 onward, leaving the first 25 years of Simic’s work to come.

Simic is prolific — his 19th book of poems, That Little Something (Harcourt), has just appeared. He has written many worthy, funny, dark, and beautiful poems. Why should we be denied him on his off days? Like so many prolific poets, he has to write a lot to write his good ones — what Elizabeth Bishop, author of 90 published poems, called “the real poems.” I’m all for the cream, but if you love a poet — and Simic’s work is loved — you want it all, if only to enjoy him at his second-best or worst and make your own selection in context. That Little Something reminds readers that Simic is a poet not of big gloomy poems but of small glooms and fears that haunt our waking lives and disturb our sleep. “I come with an expiration date,” he writes in “Eternities.” So do we all.

JORIE GRAHAM is a poet of big ambition who likes to begin her poems in weather, time of day, and some small observation of our daily flux. Since The Errancy (1997), her line has lengthened to uncoil and reach the depths and heights her spirit seeks. In Sea Change (Ecco), she has modulated her music by following long lines with three or four short lines, in-drawing like the tide, then releasing. When Graham is on, she lifts her readers, carrying them away. In this book she is writing poetry rather than stand-alone poems. When the time comes for her “selected,” it will be a hard book to make, especially when it comes to her work of the last 15 or so years, in which she is less discrete, more a poet of rising and falling, wide-angled and symphonic.