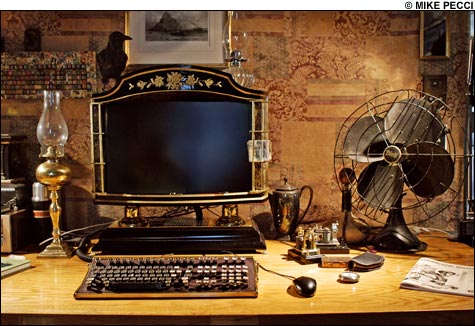

THE VISIONARY TINKERER: With help from OfficeMax and his local town dump, Jake von Slatt turned his 21st-century PC into a Steampunk marvel. |

A past that never was

These retro-future adventure themes popped up again and again as the 20th century wore on, particularly in the genre of 1970s Cyberpunk fiction, which depicts nihilistic, high-tech outlaws on the edge of society. Author K.W. Jeter coined the term Steampunk in a 1987 letter to Locus, a sci-fi magazine. “Personally,” wrote Jeter, “I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing. . . . Something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like ‘steampunks,’ perhaps.”

It wasn’t until 1990, when well-respected Cyberpunk scribes William Gibson and Bruce Sterling teamed up to write The Difference Engine (Gollancz), that Steampunk was properly introduced and brought to the forefront, legitimized as a literary movement all its own that would eventually grow into something much larger. In The Difference Engine, Charles Babbage has invented the computer (a/k/a the “analytical engine”) too early. Technically skilled “clackers” (Victorian-era hackers) program the engines with punch cards, and the suppressed revolutionaries are the Luddite anti-industrial working class. Here, the Information Age collides with the Steam Age to create something equal parts frightening and glorious, and it’s within these paradoxes and purposeful anachronisms that Steampunk lives and breathes.

I half expect von Slatt to call me m’lady as he points out the rest of his projects. “What’s neat about 19th-century industrial processes is that they are very accessible to tinkering,” he says. “Back then, you didn’t need a vapor-deposition chamber to copperplate something. All you needed was a vat of electrolyte and a battery.” During an electrolytic-etching phase one winter, von Slatt Steampunked Altoid tins, Moleskin notebooks, and even his own iPod — the stainless-steel back is decorated with an image of Lady Ada Lovelace, regarded as the first computer programmer. His larger projects dot the property around his house. An old yellow school bus he turned into “The Victorian RV” is parked in von Slatt’s backyard, and a new work-in-progress, a Steampunk play house he’s building for his daughters, is sitting a few feet away. He gleefully tells me about an idea he had that morning to construct a Steampunk canopy bed, though he won’t reveal any specifics.

There is no typical Steampunk. Its practitioners are anyone and everyone: European re-enactors, middle-aged steam enthusiasts, carpenters, illustrators, sculptors, urban clotheshorses. “I think steam engines are beautiful,” says Zachary Rukstela, a musician and industrial artist. “Steampunk was borne of the counter-culture,” Magpie Killjoy, a writer, editor, and self-described “professional ex-worker,” tells me. Libby Bulloff, an anachro tech-fetishist designer living in Indiana, has been attracted to “the tarnished decadence of Steampunk technology” for years. “I sort of see this as a big Venn diagram, with Steampunk as the box and a bunch of overlapping circles of interest,” adds von Slatt. While Steampunks — self-described or not — don’t always see eye to eye on their metaculture’s boundaries, they all have at least one crucial thing in common: a lasting, passionate fascination with Victoriana. The period roughly spans the length of Queen Victoria’s rule, when early scientific discoveries thrust society headlong into the Industrial Revolution, allowing part-time craftsmen who were captivated by the means and methods behind these inventions to advance breakthroughs of their own.