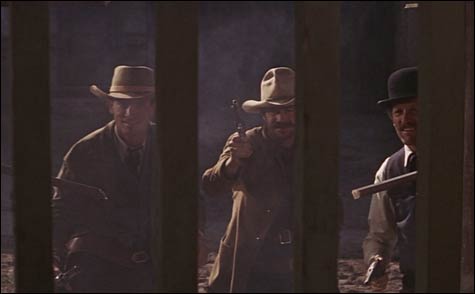

THE WILD BUNCH: In contrast with this film’s jackals and vultures, the Bunch act like men and die with honor. |

| “Sam Peckinpah, Blood Poet” | Harvard Film Archive | September 5-12 |

In the nearly two and a half decades since Sam Peckinpah’s untimely death at the age of 59, he has acquired such legendary status and his influence has been so pervasive that it’s startling to remember that he made only 14 films over a period of 22 years — and that even now many of them are still obscure. So the long-overdue retrospective that begins this Friday at the Harvard Film Archive, “Sam Peckinpah, Blood Poet,” is most welcome.

There were gaps in Peckinpah’s output owing to his uneasy relationship with the studios: fired off The Cincinnati Kid in 1965, he couldn’t get work again in Hollywood until after he’d returned to television, his original venue, and attracted critical notice with an hour-long adaptation of Katherine Anne Porter’s story “Noon Wine.” Only then did he direct THE WILD BUNCH, his masterpiece — and almost inarguably the greatest Western ever made. (The HFA will conclude the series with a screening of The Wild Bunch on September 12 at 7 pm, pairing it with Paul Seydor’s extraordinary 1996 documentary “THE WILD BUNCH: AN ALBUM IN MONTAGE,” which contains footage of the filming of the Bunch’s last stand that demonstrates how this classic sequence was assembled.) Five years turtled by between the release of Convoy in 1978 and his swan song, The Osterman Weekend. And he spent much of his too-brief career battling studio heads who insisted on dumping his pictures (like the exquisite Ride the High Country, which got relegated to the lower half of double bills) or recutting them. Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid were all released in versions he did not approve, though the last two can now be seen as he intended them to be.

Most of his TV work was on two Western series, The Rifleman and The Westerner, and six of his feature films were Westerns — seven if you count JUNIOR BONNER (September 7 at 7 pm), a fine contemporary drama in which the last vestige of the long-dead West Peckinpah eulogized in so many of his films is a father-and-son pair of rodeo cowboys superbly played by Robert Preston and Steve McQueen. The HFA has included a sample of Peckinpah’s work on The Rifleman, a gripping little episode called “THE MARSHAL” (September 8 at 7 pm, with Noon Wine). One of his enduring themes was the co-opting of the Old West. The Wild Bunch is set in 1913, the year that marked the official closing of the frontier, and its title cohort, a ruthless band of bank and train robbers led by Pike Bishop (William Holden), are its heroes. Just look at the other characters. There’s the train man, Pat Harrigan (Albert Dekker), who blackmails Pike’s old partner, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), into leading the pursuit of the Bunch, and whose carelessness gets innocent townspeople caught in the crossfire. There are the vultures Harrigan hires as Thornton’s crew of bounty hunters; there’s the power-hungry Mexican general (Emilio Fernández) who starves and terrorizes his people. The Bunch, by contrast, act like men and die with honor. Harrigan and General Mapache are both by-products of modern civilization. So is Curly (Joe Don Baker), Junior Bonner’s brother, a real-estate salesman whose only regard for his Western heritage is determining how he can exploit it. RIDE THE HIGH COUNTRY (September 7 at 3 pm), Peckinpah’s gentlest Western, is also an elegy for the Old West. By the time its two heroes, old-time cowboys and friends (beautifully played by Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott), take a job transporting gold, what used to be the West is now the stuff of arcade games and midsummer parades.

In PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID (September 6 at 7 pm), Garrett himself (James Coburn) has been compromised by progress. The governor of New Mexico (Jason Robards) makes him a sheriff and sends him out after his one-time buddy, Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson). This 1973 film, a hippie Western with a pair of pop stars — Bob Dylan, who wrote the plaintive score, makes an oddball appearance as a character known as Alias — is a fascinating failure, and though the latest (2005) restoration has clarified the narrative, the film still doesn’t work. But it’s magnificent to look at (John Coquillon shot it), and it offers indelible images and one of the director’s greatest scenes, where a deputy (Slim Pickens) expires by a stream while his wife (Katy Jurado) watches, her eyes full of silent tears, from a distance, unwilling to approach him and violate the privacy of his last moments. The sun glows crimson in the stream; Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” throbs on the soundtrack.