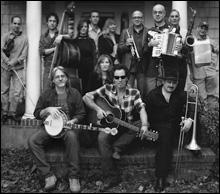

FOR PETE’S SAKE: Springsteen makes us feel the strangeness of Seeger’s songs, from the secular hymns to the children’s tunes.

|

The laugh that opens Bruce Springsteen’s We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions is the first clue that what’s about to follow might actually be fun. For those of us raised on pop, the prospect of listening to folk music has always had the same appeal as going to church: it’s worthy and maybe improving, but we don’t expect any pleasure from it. That has less to do with folk itself than with the way, starting in the late ’50s, the young white performers who were drawn to folk presented it as a pure alternative to the commercial instincts of pop, which they regarded as immature and shallow. Think of the immaculate condescension of Peter, Paul, and Mary’s “I Dig Rock and Roll Music.” On the performance of “Talkin’ World War III Blues” during his Halloween 1964 show at New York’s Philharmonic Hall, Bob Dylan gets a big laugh by referring to Martha and the Vandellas singing “Leader of the Pack.” That the Shangri-La’s actually sang “Leader of the Pack” is, for the folk audience, beside the point.Earnest, self-serious, and humorless, the approach taken to folk music has too often seemed of a piece with all the most joyless aspects of being a liberal. (You know, the Saab-driving, NPR-supporting, Nation-reading, world-music-listening, organic-market-shopping side — not to cast any aspersions.) But over the last few years, pop fans have had a chance to be delivered from that dry, constricted view of folk by the writing in Greil Marcus’s Invisible Republic, a study of Dylan and the Band’s “Basement Tapes” performances and their antecedents that reassures the reader that what always seemed strange in “old-timey” music really was strange, and in the reissues of performers like Dock Boggs, Bascom Lamar Lunsford, and those on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music.

We Shall Overcome — an album that comes across somewhere between Springsteen’s stab at his own “Basement Tapes” and a boozy, carnal wake — performs a similar sort of rescue on Springsteen’s career, which in recent years seemed to be drifting in the direction of an earnestness lacking joy. It’s worth recalling how that came about. There was a time when the very sort of people who feel simpático with Springsteen today regarded him as a throwback to what “rock music” — as opposed to rock and roll — had outgrown. In other words, he made music for greasers. And though everyone recalls how Ronald Reagan and George “Buy Me Some Peanuts and Cracker Jack” Will tried to co-opt “Born in the USA” during the 1984 presidential campaign, the number of people on the left who assented to the right-wing misinterpretation of the song as a jingoistic, America-first anthem has been conveniently forgotten. But in the midst of the Reagan years, the sight of Springsteen posing in front of the stars and stripes was meant to have the same unsettling effect Dylan intended when he draped the stages he played on his 1966 European tour with an enormous flag, as America became mired deeper in Vietnam. People who read symbols only as pro or con, black or white, couldn’t see that both Dylan and Springsteen were staging acts of reclamation. They had too much invested in their country to cede their stake in its definition. Too much of their identity was founded on what that flag stood for.

Over the years, after Springsteen reclaimed his music from Reagan, he grew into an artist who was expected to be a political spokesman, an oracle instead of a plain-talking populist. And he has often filled that role. Yet the nihilist despair that on Nebraska cut so deeply into the self-congratulation of the Reagan era gave way to the self-consciously somber The Ghost of Tom Joad and Devils and Dust. Those weren’t bad albums, but outside of their statements, they sometimes fought for independent life as music.

We Shall Overcome speaks by metaphor, tall tale, and implication and is all the more emotionally direct for it. Springsteen moves here with a sure instinct for avoiding grandiosity (the title song comes near the end, but it’s the children’s song, the deeply weird “Froggie Went a Courtin’,” that ends the album) and hero worship. It’s not Pete Seeger the revered folk icon of integrity to whom Springsteen is paying homage. Springsteen is honoring the flint it must have taken for Seeger to go his own way for so long, and honoring the faith it must take for one skinny guy with a banjo standing at a microphone (the eternal image of Pete Seeger) to sing for the idea of shared community and be confident that that ideal exists.

We Shall Overcome speaks by metaphor, tall tale, and implication and is all the more emotionally direct for it. Springsteen moves here with a sure instinct for avoiding grandiosity (the title song comes near the end, but it’s the children’s song, the deeply weird “Froggie Went a Courtin’,” that ends the album) and hero worship. It’s not Pete Seeger the revered folk icon of integrity to whom Springsteen is paying homage. Springsteen is honoring the flint it must have taken for Seeger to go his own way for so long, and honoring the faith it must take for one skinny guy with a banjo standing at a microphone (the eternal image of Pete Seeger) to sing for the idea of shared community and be confident that that ideal exists.