|

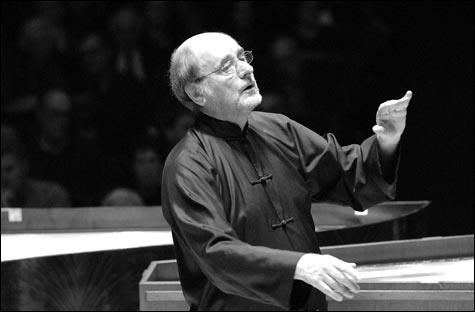

“Winter, winter, spring, and winter” — that’s what the Handel and Haydn Society’s new artistic adviser, Sir Roger Norrington, said they were tempted to called Haydn’s last masterpiece, Die Jahreszeiten (“The Seasons”), in introducing the H&H performance of it a week ago Sunday at Symphony Hall. (A week later and it might have been “Summer, summer, spring, and summer.”) Norrington also noted that H&H’s period performance of the work would boast “old instruments” (the period contrabassoon rose above the orchestra like the proposed Menino tower) and “old voices”; the latter prompted a look of mock dismay from Canadian soprano Karina Gauvin. Not missing a beat, he exhorted the audience, in the absence of other period staples like “bad wigs, lice, and terrible teeth,” to adhere to period practice and “applaud whenever you like.” It took the audience a while to warm up to that idea, but eventually it did. Do you want people applauding after every aria in Fidelio, or each movement of a Haydn symphony? Maybe not, but in a sectional work like Die Jahreszeiten it does no harm.

And Norrington, after all, is classical music’s bad-boy populist, his recent recordings with the Stuttgart Radio Symphony controversially eschewing string vibrato and making Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and Mahler sound like, well, popular music. There’s less to be milked from Die Jahreszeiten. First performed in 1801, the oratorio follows a conventional course: spring buds and blooms, summer survives the noonday heat and the inevitable thunderstorm (none of Vivaldi’s gnats, though), noble toil produces the autumn harvest and the love pledges of Hanne and Lukas and then the hunt, and winter finds the wanderer exposed to the elements before he spies a cottage where villagers have gathered and Hanne tells how a chaste maid outwitted a lusty squire. We’re reminded that the old age of winter awaits us all; only virtue lasts, and as the piece ends the virtuous go marching into Paradise.

As Simon, who unlike Lukas doesn’t have a sweetie, Austrian baritone Günther Groissböck belted out his opening recitative about the sun in Aries as if it were the “O Freunde” of Beethoven’s Ninth. He provided the requisite depth and gravity, and German tenor Christoph Genz was a light and sweet Lukas, though he could be heavy when necessary, as in the sultry, sluggish opening to “Summer,” and he gave full value to the “starr und matt” (“numbed and wet”) of his winter-wanderer aria. As Hanne, Karina Gauvin, in a refreshingly simple and undistracting heliotrope gown, had a gorgeous tone and gave point to the text without being pedantic; in her “erquickendes” you could hear a cool summer gust. I only wish she had looked at Genz during their autumn love duet. Norrington seemed determined to prove that Baroque is bracing rather than boring, throwing the audience a sly look when a Papageno-like German folk melody turned up, drawing out the reedy humor of the word “Rohr” (“reed pipe”), giving us loopy horns here, a majestic sunrise chorale worthy of Bruckner there, crisp fugues everywhere, making sure we heard the lambs and the fish and the bees and the butterflies and the crickets. And he got results: during the plucked strings of Hanne’s anticipating-the-summer-storm aria, normally cough-happy Symphony Hall was so quiet, you could hear a raindrop.