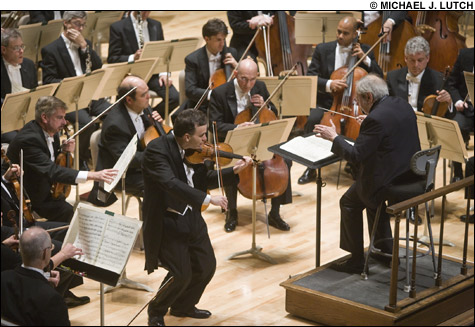

RICH-TONED STRAVINSKY? Gil Shaham and André Previn teamed up for the Violin Concerto. |

There was hardly a concert I was more eager to hear than the Celebrity Series of Boston’s celebration of pianist Leon Fleisher’s 80th birthday. This profound artist (a student of Artur Schnabel) is also a scintillating technician. His recordings are legendary. And so is his story: the loss of the use of his right hand (from focal dystonia) in his prime, his four-decade search for a cure, his conducting, his performances of the left-hand repertoire, his finally regaining some use of his right hand, his becoming a 2007 Kennedy Center Honoree. He’s now giving 80th-birthday concerts he calls “Leon Fleisher & Friends,” with three of his former students: the Soviet-born Israeli virtuoso Yefim Bronfman, the insightful young American Jonathan Biss, and Katherine Jacobson Fleisher, his wife. At Carnegie Hall, they played the same program we heard two days later at Jordan Hall. I was expecting to love it. I’m sorry to say I didn’t — at least, not all of it.

“In these times of turmoil,” Fleisher announced, it would be “salutary” to offer a “Triple-A” concert: “Anthems Against Acrimony,” a series of calmly passionate works ending — not calmly — with Ravel’s own piano transcription of his cataclysmic La valse. Fleisher’s most satisfying and moving performance was his first, pianist Egon Petri’s heavenly transcription of Bach’s “Sheep may safely graze” (a soprano aria from a secular, mythological cantata), with some of the keyboard’s most exquisite counterpoint. Fleisher hasn’t lost his touch — no other pianist has that glittering, limpid, instantly identifiable tone and the unfussy yet uncannily illuminating phrasing. Even playing the same piano, the other three never sounded like him.

The Bach was Fleisher’s only solo. He played four-hand pieces with each of his partners (always at the low end), in alternation with their own solos. Bronfman delivered a supple but mild Schumann Arabeske and Biss a strong Beethoven E-minor sonata (Opus 90) with a particularly rhapsodic second movement. But Jacobson Fleisher made Mozart’s sublime A-minor Rondo seem uneventful, with little sense of emotional content or dramatic arc. (Schnabel has the great, bone-chilling recording.) Biss joined Fleisher in Schubert’s F-minor Fantasie, but this infinitely piercing piece somehow wasn’t very moving. Was it too fast? Too slow? (A piano-playing friend pointed out that Fleisher’s domination over the pedal prevented Biss from making any dynamic changes in the melodic line.) Fleisher and Bronfman gave us Dvorák’s piano versions of three lively and rapturous Slavonic Dances, but they were more lilting than rapturous. With Jacobson Fleisher, in La valse, Fleisher supplied the deep subterranean rumbling, and the piece, with its lightning glissandos, worked up a real head of steam. But all the switching around, elegant on paper, defeated momentum, and frankly, I just wanted to hear more of Fleisher on his own.

Boston’s senior musical organization, the Handel and Haydn Society, is entering its 194th season. It’s had an unusual number of leaders in recent years: early-music celebrity Christopher Hogwood, former BSO assistant conductor Grant Llewellyn, and, as artistic adviser, Sir Roger Norrington. H&H has just announced a new director, British conductor Harry Christophers, who made a hit with last winter’s Messiah. His tenure begins next season, but he just led a delightful Handel program at Symphony Hall, alternating Handel’s four Coronation Anthems (composed for George II) with festive choruses and soprano arias from later operas and oratorios. The music called more for energy and elegance than for probing interpretation, and that’s what he delivered.

Christophers is the founder of the popular vocal and period-instrument ensemble the Sixteen. He’s a lively presence, physically uninhibited yet rhythmically precise. (From my balcony seat near the proscenium I could see even his eyebrows conducting.) The articulation of the H&H chorus was especially impressive, and the orchestra played with forthrightness and power, with outstanding work in the more public pieces by timpanist John Grimes and the three trumpeters, Bruce Hall, Jesse Levine, and Paul Perfetti, plus some seductive flute playing by Christopher Krueger. Canadian soprano Gillian Keith has a pretty if not notably distinctive voice, but she caught the pre-tragic naïveté of Iphis and the ingénue in Jephtha, and, wittily twirling her lavender sash, she nailed the coloratura in Semele’s self-congratulatory “Endless pleasure” and “Myself I shall adore.”

Next year marks the 250th anniversary of Handel’s death and the 200th of Haydn’s, so Christophers is promising a season devoted to H&H’s namesakes. No objection from this corner.

Something old, something new . . . The clerestory lunette windows at Symphony Hall were boarded up in the early 1940s (probably for wartime blackouts). But the boards are now gone, and natural light comes pouring into the auditorium the way it was intended to. The color is warmest at twilight, when the sky is deep cerulean. I thought I was imagining that the sound too seemed brighter, but other good listeners have mentioned this as well. No doubt every surface of the hall, which includes the clothed and unclothed statues (now better lit), contributes to the phenomenal acoustics.