The climate is tropical, sweet skunk fills the air, and reggae jams are hitting such lofty decibels that I can't even feel my phone vibrate. To my right is a college kid with foggy black frames, dancing like a drunken ostrich. Beside him is a sexy tattooed co-ed, advertising her nipple rings through a sweaty tan tank top. And to my left — halfway across the room — is an island dude sporting the single fattest dreadlock that I've ever ogled. Contrary to what I would have expected, white boys are swigging Red Stripe, while Rastafarians are sipping Budweiser. "Just understand dis," one regular tells me: "It's cheapa."I'm not in Montego Bay, or even South Florida, where at least palm trees and sweltering heat manifest convincing Caribbean illusions. I'm at the Western Front in Cambridge, eight blocks outside of Central Square and about 2000 miles from Trenchtown. And this is a typical Friday night here at the Front, where reggae and West Indian music have invigorated (and also aggravated) neighbors of the residentially situated two-story club every weekend for almost four decades. Halfway through the show, as Lady Lee (Boston's only prominent female reggae MC, or "toaster") cues her band and grabs two comparably angel-lunged male cohorts, Ajahni and Toussaint, for an encore, the spectacled kid — slipping into a sudden Pentecostal-esque spell — faints in the arms of his chesty homegirl. The music is so consuming, though, that hardly anybody notices. So, noble Samaritan that I am, I leave my Red Stripe on the bar and drag him to the bathroom to splash tap water on his face.

Reggae is now a much neglected genre. There are rarely any stories on local or nationally touring reggae acts in Boston's dailies, and there's not even a Boston Music Award for Outstanding Reggae Act. In fact, since its boom in the late 1970s — thanks primarily to the ascension of Bob Marley to international superstar and Third World ambassador, but also to a number of British artists (from Eric Clapton to the Clash) incorporating or covering reggae in their work — reggae has been marginalized by the pop-culture crowd. It's been written off as a musically adolescent tangent for slackers and hippies too stoned to know the difference. But it still has the power to mesmerize (and to cause seemingly able-bodied men to pass out).

Case in point: while the mainstream has slept on reggae, Beantown's roots and dancehall scenes are blazing, nursed by both a loyal and ever-growing West Indian population and an adventurous college demographic. There are even signs that reggae is once again ready to bite a serious slice of commercial pie in the Boston market. Recently, roots-dancehall hybrids (and North Shore natives) Nomad-I and Mighty Mystic packed the Paradise in February; the new House of Blues drew more than 1800 heads for once-Boston-based white-reggae outfit John Brown's Body in April; and fans from Lynn to Roxbury got their first dedicated Caribbean radio station, the pirate Big City 101.3 FM, in 2007. This summer's concert schedule is loaded with reggae events, from Burning Spear and Beres Hammond, to Shaggy and Caucasian prodigy Collie Buddz in June, many of which will sell out the city's largest arenas. Berklee-spawned Boston reggae champions Hot Like Fire will celebrate their 20th anniversary next Friday. Through it all, Blue Hill Avenue remains a booming and authentic strip for cutting-edge Caribbean riddims.

The future of Boston reggae — let's call it Hub Dub — would thus seem bright as Negril at noon. But a lack of consistent brick-and-mortar outlets for live shows (thanks to a debatable reputation for violence that has scared off more than one club owner) has reggae on the run. The latest blow to rock both artists and promoters was the recent shuttering of Bill's Bar on Lansdowne Street, which had been downtown's sole go-to reggae joint since 1995. Still, fans refuse to put defeat in their pipes and smoke it. Thanks to this city's significant place in reggae history, to the current set's increasingly diverse makeup, and to the fundamental Rasta tradition of overcoming adversity, indications suggest that Boston's dutty-rock contingent will continue to get up, stand up, and dance its ass off.

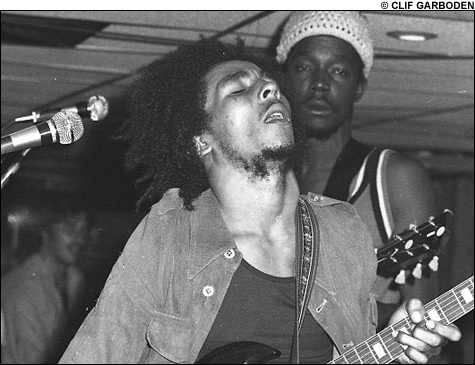

On 1973, reggae icon Bob Marley played at the now-defunct Paul’s Mall on Boylston Street as a genre pioneer. |

The early years

If TheRocky Horror Picture Show owes much of its iconic cult status to New York City (where the flick played weekend midnights at the Waverly Theatre for 95 weeks starting in 1976), then Cambridge can take credit for helping usher reggae into America's alternative consciousness. In 1972, film director Perry Henzell had the world premiere of his seminal Jimmy Cliff reggae-gangster flick, The Harder They Come, at the dearly departed Orson Welles Cinema on Mass Ave in Harvard Square, where it ultimately ran for eight years. That's also the theater where, in 1976, WBCN sales rep Kenny Greenblatt surprised moviegoers by delivering Cliff in person after he played a set at the Orpheum.