JAZZ UNPOLICED The man was serene, but the band took the Cohen songbook — often a thing of minimalist beauty — and trampled it. |

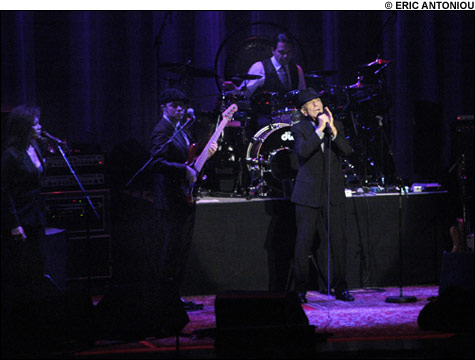

The anticipatory mania burst last Friday night when the man himself finally strode gingerly across the stage. A dapper and sophisticated 74-year-old in a tailored double-breasted suit and Sinatra-y fedora, Leonard Cohen grabbed his microphone as his band slipped into the slow jig of "Dance Me to the End of Love." He crouched down, almost but not quite on bended knees, as his low craggy voice serenaded the heavens, cutting a pugilistic figure halfway between a rock singer machine-gunning lyrics at his audience and an old man crouching to place flowers on a woman's grave.If your exposure to the music of Leonard Cohen consists mainly of listening to the sparse arrangements and quivering nasalities of his late '60s/early '70s albums, this show might have been a shock. First, Cohen's voice is, at his age, not the voice of that younger man. Whether he is singing or speaking between songs, it is a constant low grumble, both intimate and mysterious. Of course, in the world of pop music, Cohen was never a young man (he was 34 when his first album, 1967's Songs of Leonard Cohen, came out), and he was never really a singer in the conventional sense. He has emerged four decades later as a world treasure, known for his lyrical mastery and his deft mix of melancholy and wit. On Friday, after a passionate run through 1992's sinister "The Future," he quipped "The last time I was here in Boston I was 60 years old — just a kid with a crazy dream."

The second shock would have been the arrangements of Cohen classics by his current backing band. At first, the feel was tasteful, reverent. The band kept things at a simmer, putting Cohen's gravelly boom front and center. But by the third tune, "Ain't No Cure for Love," a switch seemed to have flipped in saxophonist/multi-instrumentalist Dino Soldo, who proceeded to splatter the song with painful David Sanborn-isms that were jarring and bizarre. Unfortunately, this foray into smooth jazz hell was no brief detour. Over the course of a three-and-a-half-hour set, the band proceeded to take the Cohen songbook — often a thing of minimalist beauty, naked save for guitar and voice — and overwork it until you felt trapped in an endless elevator with an '80s iteration of the Saturday Night Live band.

The audience didn't seem to mind hearing their hero's music pulverized into a Dylan at Budokan horror show. In a sense, it was enough just to be in Cohen's serene presence. There is something otherworldly about a Cohen show, unlikely and unrepeatable, and it had this crowd under its spell. This, I suppose, explains the rapturous applause given every squall of the Kenny G wedding band, as they took somber material like "Who By Fire" and tacked on mood-shattering blues licks and other distractions, finally hitting a nadir two-thirds through the show with "Boogie Street," a painful sub-Sade atrocity led vocally by back-up singer and frequent Cohen collaborator Sharon Robinson.

But the set, like so much of Cohen's work, also contained moments of redemption. "Hallelujah" was as uplifting as a rendition by its maker could be, and as Cohen gets older, his delivery just grows more and more profound. Near the end of the set proper (there would be a whopping three encore sets!), Cohen declared, "You came to me this morning and you handled me like meat." The ensuing read-through of song-poem "A Thousand Kisses Deep," a bare, spoken meditation on the frailty of love and memory, was elegant, poetic, and mercifully free of sax punctuation. ^