Critics of the planning process for Fort Point during the past decade might argue that artists haven't had a seat at a round table at all, alongside developers and city officials, but have rather been relegated to the kiddie table, where they are indulged but not taken seriously.

By the turn of this century, billions of dollars had been pumped into the South Boston waterfront area — the Central Artery tunnels, the Silver Line, the Boston Harbor clean-up — and developers were lining up to reap the benefits of Downtown Boston's new frontier, including Menino, with his plans to relocate City Hall to South Boston in tow. At the same time, since the old industrial zoning was being completely rewritten, the BRA should have had considerable leverage in guiding the direction of development. Two years ago, after thousands of hours of planning meetings, the BRA unveiled its "100 Acres" master plan, designating the whole district a Planned Development Area, giving the BRA extraordinary latitude to approve projects on a case-by-case basis. Reflecting the consensus of residents and artists, the BRA laid down core principles for development, including that new projects "be at least one-third residential or artist live/work in character."

Among the signatories to the 100 Acres plan was a real-estate company known, ominously enough, as Archon, a partnership between the Archon Group — a real-estate subsidiary of the Wall Street investment-banking and securities firm Goldman Sachs — and Tony Goldman (no relation), a fancy-pants developer who takes credit for the gentrification of New York's SoHo neighborhood. In a 2006 New York Times article, he described his grand vision to transform Fort Point into "the Wharf District," where high-end condos, boutiques, and galleries would co-exist with edgy artists.

But within a couple years of buying 14 buildings in Fort Point, totaling more than 1.2 million square feet, Archon sold off the bulk of its "portfolio," and most of the development the BRA has signed off on has been for office conversions, a clear violation of the one-third residential component of the envisioned plan. Goldman's partners were more direct in laying out their strategy for Fort Point: obtaining concessions from the BRA and flipping most of the buildings. "Archon's development team is working through the Boston Redevelopment Authority . . . to obtain an additional 500,000 SF of FAR [floor-area ratio] for three of the buildings," its Web site boasts. "Once zoning approval of the additional FAR is complete, these assets will be sold." In other words, while Archon and other developers have touted the cachet artists bring to Fort Point, they have generally treated the real-life artists living there as an impediment to developing or disposing of their assets.

Messages left with Goldman and John Matteson, Archon's regional director of acquisitions, were not returned.

The BRA maintains that it is committed to the 100 Acres plan. Kairos Shen, the BRA's director of planning, notes that the approved projects represent only an early stage in what may eventually comprise six million square feet of development stretching over the whole waterfront area. "Nowhere did we say that residential had to go first," he says. "Much of these plans depend on what financing is available. The 100 acres may take 40 years to build out."

Whether artists will still be around then, of course, is an open question, but the current trajectory doesn't bode well.

"It's a frustrating thing," says Jon Seward, an architect and planner in one of the buildings due to be cleared out. "We're the ones who put up with the squalid conditions. Now that billions have been spent cleaning up the harbor and on the Silver Line, they expect us to dutifully and meekly make our way out through the back door, so the big money can get made."

Seward has been in the neighborhood long enough — nearly 20 years — to remember when Rick James played at the Channel, the local rock club, and when artists, dock workers, and the occasional downtown suits drank together at Lucky's bar.

Seward points out that it's not just artists that called the district home, but scores of arts-related businesses and organizations. One of the nonprofits that was forced out was the Revolving Museum, which put on arts programs for inner-city kids. The museum is now in Lowell. Fort Point was also the nurturing ground and remains the home for many internationally renowned artists. One of them, Harriet Casdin-Silver, a pioneer in holographic art, passed away this past year, not long after being kicked out of her studio. In a measure of the acrimony in the neighborhood these days, Goldman was accused by artists at a community meeting in March of contributing to her death due to stress.

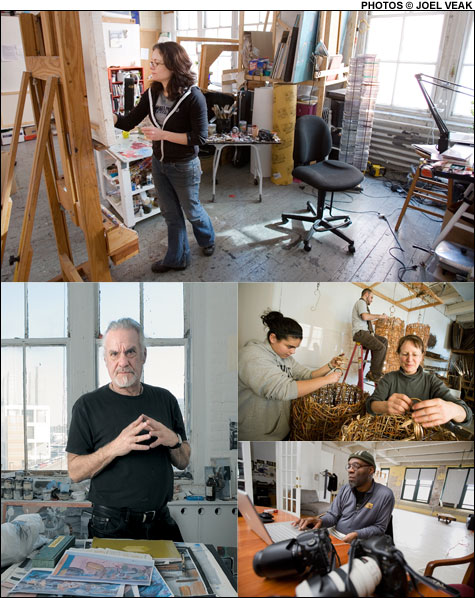

HERE’S THE POINT (Clockwise, from top) Amy MacDonald, Katherine Ahearn (with Wentworth co-op students Pat Ramey and Carla Vasta), Tony Owen, and Stewart Diamond — just a handful of the artists living and working in buildings on A Street that are due to be cleared out under a BRA relocation plan. |

Move 'em all out and shake 'em up

Paul Bernstein, the president of the Fort Point Arts Community (FPAC), the neighborhood's main artist-advocacy group, was at that meeting, and many others this past year, imploring city officials to get involved in lease negotiations on behalf of 77 artists whose leases were expiring near the end of November.