NO FUN: Butterworth’s important and informative book about anarchy is . . . anarchic. |

| The World That Never Was: a True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists & Secret Agents | By Alex Butterworth | 528 pages | Pantheon | $30 |

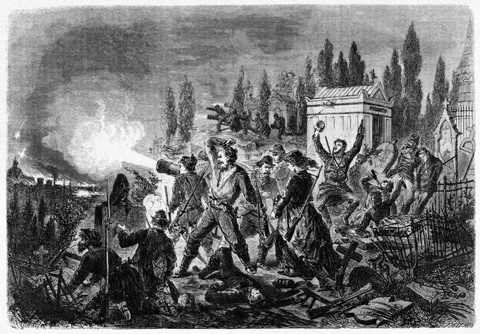

Some marketing wizard gave Oxford-based historian Alex Butterworth's exhaustive history of the international anarchist movement a fun title it doesn't deserve. This book, following anti-authoritarianism from the failed 1871 Paris Commune to the Second World War, is not fun. It's interesting, important, impressively (too) thorough, fair, and eye-opening, but far from the "Spy vs. Spy" romp through European socialist dogma that its extended name suggests.

The World That Never Was part is dead on target, and "The Big Historical Force You Never Understood" would have been a decent, though clumsy, alternative. What you will learn (and you've been warned, reading it will be a bit of a "good for you" slog, since Butterworth is no stylist) is that anarchism — before the autocrats and democrats it threatened bastardized the term into something interchangeable with communism and synonymous with terrorism — was a thoughtful and, originally, non-violent political philosophy based on a belief in the perfectibility of man.

"Anarchism" comes from a Greek word meaning "without rulers." Its understandably disparate architects and advocates — a few whose names you may have heard, such as Mikhail Bakunin, Prince Peter Kropotkin, and Élisée Reclus, and a multitude who survive only in obscurity — opposed the revolutionary factions who, adhering to the writing of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, espoused a top-down new world order that relied on a strong, centralized communist state. Down that path, of course, lurked tyrants like Stalin and decades of "reform" corruption by hypocritical party officials. Not to mention considerable violence.

The communists dismissed the anarchists — who at their core were not abused peasants but compassionate and educated scientists and philosophers riding the rising tide of Darwin-inspired rationalism — as foolish Utopians doomed to failure. The anarchist camp subsequently made two important decisions: to adopt officially (at the in-your-face urging of anarchist spokesperson Élisée Reclus) the label of "anarchists," knowing full well it carried pejorative baggage; and to abandon non-violence and embrace political assassination as a necessary tactic. Thus was the exaggerated popular image of bomb-tossing anarchists consolidated (and somewhat justified).

Butterworth covers all this and more in a text that's less like a narrative and more like a 400-page series of previously neglected facts — some momentous, many inconsequential. You can't possibly remember them all, never mind prioritize them. The book is prefaced by a glossary of more than 100 mostly tongue- and mind-twisting names and mini-bios of political players. It would seem that we're meant to memorize these 17 pages of dramatis personae so things will fall into place when Butterworth refers to one by surname 250 pages later.

It's a shame that The World That Never Was invites readers to give up in helpless confusion, because this is a sector of history that's long been withheld and purposefully misinterpreted. It's important stuff and good to know, but the book is far from a relaxing summer read. If you take it to the beach, be prepared to curse the sand you lie on.

CLIF GARBODEN is a non-violent anti-authoritarian freelance writer.