WHAT IS REAL? Images from the Collision series. |

On Saturday, the eighth anniversary of the start of our Iraq War passed mostly without notice except for some smallish protests in Providence, Washington, and elsewhere. It was easy to overlook as Japan continued to struggle with an earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear plant meltdown, and the US Navy began firing cruise missiles at dictator Muammar el-Qaddafi's Libya as part of a United Nations-sanctioned intervention into the civil war there.

But our wars haunt Providence artist Jay Zehngebot's show "Our Sentry," a pop-up gallery exhibition organized by R.K. Projects (65 Eddy Street, Providence, through March 26), which Tabitha Piseno and Sam Keller launched last October to put on brief art exhibits around town.

Our war-making has grown increasingly automated as we hunt our enemies with cruise missiles and remote-controlled drone planes. This has corresponded to a rise in military computer simulations that echo the art and technology of video games. Here Zehngebot mulls the muddled overlap between real and virtual combat.

Zehngebot studied printmaking at RISD, has been involved with the Trummerkind collective, the folks behind the infamous secret apartment at the Providence Place Mall, and makes work at the AS220 Printshop. Coming out of school in 2007, his drawings and prints (like a monster featured in the 2008 anthology Beasts! Book 2) were often sci-fi creature fantasies in a sketchy, obsessive Fort Thunder style.

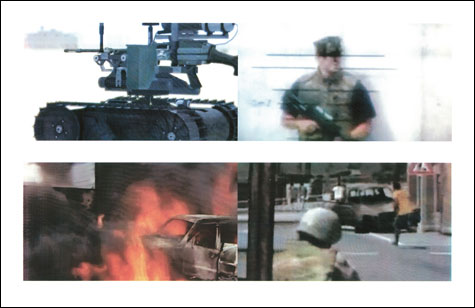

WHAT IS REAL? Images from the Collision series. |

"Our Sentry" finds Zehngebot screenprinting photographic imagery. He pairs a shot of a burning car from a PBS special with an image from the video game ArmA2 of a mercenary taking aim at a fleeing protester. Another print from this Collision (Game/Video) series pairs a shot from Battlefield: Bad Company (the images generally come from YouTube videos of gameplay) of two soldiers inside a helicopter with an image from a PBS documentary showing fighters who have slid down a rope onto a rooftop from a helicopter hovering above. Zehngebot's process purposely reduces the images' resolution to "blur the boundary between these things," he tells me.

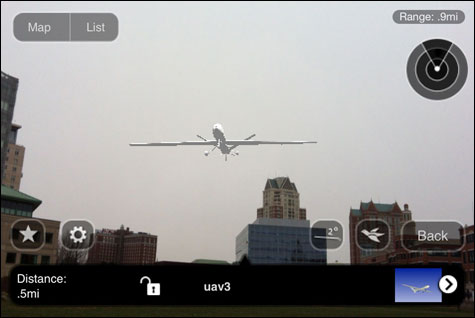

A grainy image of a helicopter apparently hovering over a minaret comes from the Hezbollah-produced game Special Force, which simulates Hezbollah fighters repelling an Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Elsewhere he reproduces images of a soldier avatar used by the US military in recruitment presentations as well as for training therapists to treat veterans psychologically scarred by war. For Jujitsu-Drone, Zehngebot figured out how to include a digital model of a Predator drone in photos he took with his iPhone and used the process to create eerie images of drones gliding over downtown Providence.

But the sources of the imagery and the fact that some photos are real while others are virtual — background info vital to the art's power — are unclear from the art itself, and remain a bit confusing even after reading wall texts and a handout. And why further blur the differences between the real and virtual images when the marvel of the digital shoot-'em-ups is how authentic they already appear?

UNFRIENDLY SKIES Zehngebot's Jujitsu-Drone. |

There is debate in the art world over how much art needs to speak for itself (or at least point to its references) and how much to let curatorial texts explain things. I tend to think art should be able to stand on its own, that it should embody its meaning.