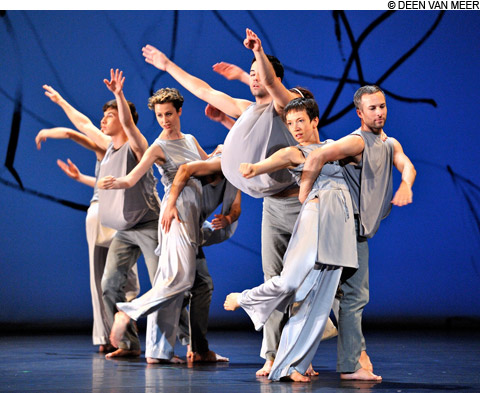

LES YEUX ET L’ÂME Trisha Brown’s setting of Rameau didn’t echo the Baroque dance rhythms, but

the stage pulsed with the music’s billowing, lilting flow. |

Two dance generations separated the performances at Jacob's Pillow two weeks ago, but Trisha Brown, Jodi Melnick, and David Neumann have a lot in common. Brown, a founder of postmodern dance, evolved out of the raucous Judson Dance Theater and the improvisational Grand Union into an experimenter concerned with the basics of physicality, perception, and space. She turned everyday movement upside down and inside out, eventually devising an elastic, multi-directional, and expressively neutral dance style.Brown's company presented a mini-survey of her development since the '70s, including the ironic, minimalist Spanish Dance (1973); Set and Reset (1983), with a montage of film clips on overhanging screens by Robert Rauschenberg; and Foray Forêt (1990), originally accompanied by a band marching outside the theater (recorded in this case).

Brown's newest work, Les Yeux et l'âme, is a suite of dances from Jean-Philippe Rameau's opera Pygmalion, which Brown directed in Europe last year.

Brown doesn't choreograph on the music so much as over it. The four men and four women — in flowing grey pants and tops — glide and pause graciously, molding alongside their partners' bodies like friendly cats. They don't echo Rameau's Baroque dance rhythms, but the whole stage seems to pulse with the music's billowing, lilting flow.

Music was a take-it-or-leave-it thing for the postmoderns. Brown's dances, and those of Melnick and Neumann, could be comfortable in silence, ambient noise, or manipulated vocals like Laurie Anderson's score for Set and Reset. There's a lingering wariness about music among some dancers, as if it might overpower them if left to its own devices. But sometimes they allow its beauty in, unabashed.

David Neumann's 2006 Hit the Deck (Studies and Accidents) offered teasing "prepared" selections and whole numbers from Stravinsky, performed by intrepid pianist Carol Wong and tenor Timothy Fallon. The musicians romped through several piano pieces — including a mash-up of endings, a duo played on and inside the piano, a selection with dropped notes — and the dancers followed in their own way. Then, as Natalie Agee danced a solo, Fallon stood quietly by the piano and sang the "Pastorale." I was stunned, as much by his gorgeous, effortless vocalise as by the fact that it was there at all.

Neumann and Melnick, like their predecessor Brown, create dance from their own bodies and experience, bypassing balletic refinements and tricks. At least two pieces on their shared program were meant to draw our attention to their distinctive movement styles.

Melnick's Fanfare (2009) was a long solo of gestures and quirks and elegant ventures into a space that contained nothing but two whirring fans. She might have been imagining or invoking an absent partner when Dennis O'Connor walked on. They began a unison duet of pliés and hops, and he seemed to be following her lead. O'Connor, who formerly danced with Merce Cunningham, now teaches yoga, and the phrase they were doing began to look like yogic stretches and salutations. Though they were doing the same thing, he looked much lighter and less spatial than the detailed, rigorous Melnick.