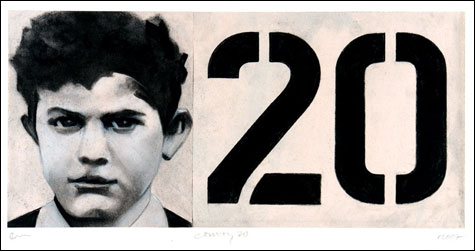

“CONVOY 20:” Charcoal and chalk by Robert McKibben. |

| “History” | drawings by Robert McKibben | through June 21 | at Filament Gallery, 181 Congress St, Portland | 207.774.0932 |

Robert McKibben has spent a good-sized piece of his life reviewing movies, but judging from his show of drawings, “History,” at the Filament Gallery in Portland, he hasn't suffered any ill effects from such a long immersion in the warm lard of Hollywood offerings. This show has a subtle but relentless energy that emerges slowly.The basic thesis is straightforward. McKibben has made drawings based on photographs and arranged the images to reflect his own meditations on the subjects. The core group is photographs taken from Serge Klarsfeld’s book French Children of the Holocaust (NYU Press, 1996). Klarsfeld collected some 2500 photographs of the 11,000 Jewish children who were interned in a holding camp at Dancy, in Vichy-controlled France, during World War II, and deported in convoys to death camps, mostly Auschwitz.

McKibben shows his drawings of these photographs paired with a stenciled number that is the same size as the picture. The number looks like it could have been an identification code stenciled on a railroad boxcar. It evokes an atmosphere of crude mechanical systems employed in the service of a ruthless bureaucracy. No one would use numbers like this except to keep things in order in the simplest and cheapest way possible.

By choosing to draw these images McKibben has required himself to concentrate his attention on them for long periods. Drawing a face carefully means that you have to look at it carefully, finding nuances of light and shadow to create the information that we can recognize as a face. By drawing them he has had to come to know these faces extremely well. By exhibiting them, he has invited us to share his detailed experience of engagement with the images, and to contemplate with him the children’s grim fate.

The stenciled numbers accentuate the sense of what Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil.” Making and presenting the drawings of the doomed children is a simple but thoughtful memorial, the opposite of banality.

Arendt comes to mind again in McKibben’s drawing “Masters of Autarchy,” a dual portrait of Hermann Göring and Martin Heidegger, rendered with a hint of family resemblance. Göring, of course, was a Nazi political leader, Luftwaffe commander, and Hitler’s designated successor. Heidegger, whose philosophy was central to development of deconstruction and postmodernism, was a member of the Nazi party until the end of World War II. Arendt, who wrote an important work on totalitarianism, had been a student and sometime lover of Heidegger’s and had testified in his behalf at his de-Nazification hearings so he could continue to teach. McKibben’s drawing is a reminder of the simple fact that one of the founding figures of current academic thought was an unrepentant Nazi.

McKibben also turns his contemplation of the ironies of history toward the left. In “A Saint of the Revolution,” he has drawn the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who had been a leading propagandist and activist in the early years of the Russian revolution. Mayakovsky, in his disillusionment over Communism, committed suicide in 1930. He is shown here paired with a skull. It brings to mind the grim Stalin-era joke: What were Mayakovsky’s last words? “Don’t shoot, comrade!”