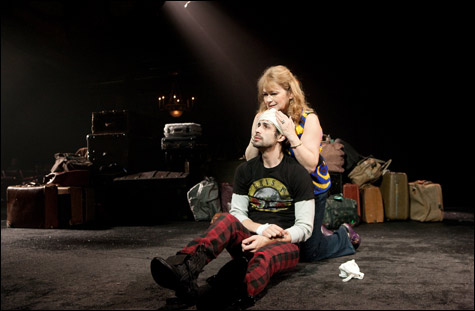

MOTHER AND SON I: Mickey Solis and Karen MacDonald get fetal in The Seagull. |

The Seagull begins with a theatrical experiment — a brief symbolist drama dreamed by young Konstantin Treplev, who's struggling toward artistic expression while endeavoring to showcase his girlfriend and impress his actress mother. But at the American Repertory Theatre, where Hungarian director János Szász delivers a vision of Chekhov's compassionate 1896 tragicomedy that's both jangling and stately (at the Loeb Drama Center through February 1), the curtain does not go down on Konstantin's evocation of a dead planet dominated by a universal soul when his bored mother gives it a contemptuous yank. The world inside the floundering artist's head becomes the world of the play: beautiful, dilapidated, fighting its way into being. The whole play is conceived as an angry, angst-ridden flashback ended by the rifle blast with which young Konstantin ends his life. Is this a radically skewed vision of Chekhov's great ensemble paean to artistic creation and unrequited love? Yes. Does it work? Also yes.

Of course no one comes to the ART expecting his grandfather's Chekhov; here you don't even get Konstantin's mother's Chekhov. At the heart of the production, which is placed by scenic designer Riccardo Hernandez in a decaying theater 200,000 years hence (the period of Konstantin's dramatic ditty), is the Oedipally driven son's contempt and reverence for his mother's art form: contempt for the showboating melodramas in which she plies her trade and attempts to perpetuate her youth; reverence, signified by the hovering presence of cracked murals inspired by Andrei Rublev's 15th-century icons, for what "new forms" might render possible upon the stage.

Szász's production is propelled by these emotions smacking up against each other as David Remedios's sound design moves between near-religious cadences dominated by jazz horns and cacophonous rock and roll, with Konstantin playing air guitar on his rifle as the punk-tinged younger characters gyrate in a lonely, communal frenzy that not even the destructive rain that thunders into the rotting theater at the end of Chekhov's act three can quench. In a Seagull that pushes emotional and sexual subtext (sometimes too hard), it is the older generation, clinging to fading youth and a power made possible by trifling fame, that is made to seem ludicrous. Konstantin may initiate the action by letting fly an avant-garde faux pas; he may have more passion than talent. But, buffeted by love and art, he is Szász's hero.

So, this Seagull, its characters slouched in rows of mottled-red, weatherbeaten theater seats when not pushing them around or stomping in and out of the mise en scène through puddles, is not for Chekhov purists. And, truth to tell, there are a lot of choices when it comes to productions of this first of the Russian playwright's quartet of turn-of-the-20th-century masterpieces — a desperate, comic roundelay of artistic talk and misdirected passion built on Konstantin's loss of provincial muse Nina to his mother's boyfriend, the dallying literary mediocrity Trigorin. (Chekhov characterized the play as containing "a great deal of conversation about literature, little action, tons of love.") Last fall a reportedly exquisite period staging by Ian Rickson, first mounted for London's Royal Court Theatre, garnered ecstatic reviews on Broadway. And Boston's Publick Theatre mounted a respectable al fresco production last summer in which the Charles River stood in for Chekhov's lakeside setting. But Szász's vision of the play, though it casts some of the characters in a harsher and more violent light than Chekhov does, has a peculiar majesty — one that marries the avant-garde of 100 years ago, exemplified by a winged Nina cranked aloft by a pulley in the play within the play, to the no-more-masterpieces experimentalism that has been a defining characteristic of the ART.