Boston Ballet's Jewels at the Wang Theatre.

By JEFFREY GANTZ | March 4, 2009

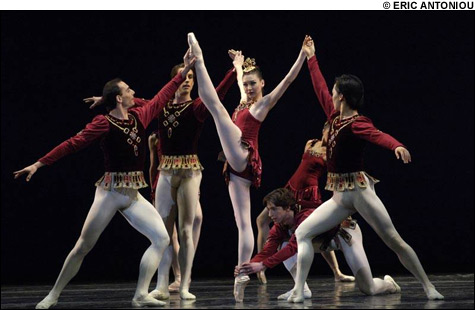

RUBIES: Kathleen Breen Combes was too much for her hunters in the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors section; she also impressed Alastair Macaulay of the New York Times.

|

In 1967, George Balanchine created Jewels for New York City Ballet, and in short order this evening-length triptych — Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds — became the crown jewel of 20th-century dance, three ballets that add up to one, glitter that’s also gold, a “plotless” work that’s really a bottomless well of stories. Boston Ballet has staged Rubies on four previous occasions, but never Emeralds or Diamonds. Now it’s finally offering a complete Jewels (at the Wang Theatre through March 8), and if Emeralds is so far a little pale, Rubies and Diamonds confirm the company’s international stature, the latter crowned by three laceratingly intimate performances from Kathleen Breen Combes and Yury Yanowsky. Here’s how the first weekend shook out.

EMERALDS | Its eight parts set to Gabriel Fauré’s incidental music for Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Edmond de Haraucourt’s Shylock, Emeralds is Paris and France. Its elements are earth and water; its backdrop is hunter green with a champagne-curtain frame; its mood is dreamy, almost somnambulistic. Found in a forest, Maeterlinck’s Mélisande is a mystery woman who loses her crown in a well and her wedding ring in a fountain — in other words, she’s half woman and half water fairy. (In another Maeterlinck play, Mélisande is one of Bluebeard’s escaped wives — Balanchine had fewer wives than Bluebeard, but not by many.) Emeralds’ solo for the first lady is music Fauré wrote for Mélisande at the spinning wheel (spinning straw into gold?); the Sicilienne for the second ballerina represents the scene where Mélisande loses her wedding ring; the second couple’s “clock” movements in the “step” nocturne duet (an kind of unmarked polonaise) suggest that time has come to the forest. Up to that point it’s been the forest before the Fall, but then predators arrive in Paradise, in the form of Fauré’s hunting horns — Man, or Love, or both.In 1967, there were just six sections to Emeralds; in 1976, after Suzanne Farrell had left NYCB and then returned, Balanchine added the “Epithalamion” from Shylock and, as the final section, Fauré’s music for the death of Mélisande. The 10-woman corps disperses; the two lead couples and the pas de trois man and two women process in funereal majesty. The lead men exchange partners; then the pas de trois ladies run out at the back, and the lead women follow them. The three men go to one knee and extend their right hands — only they’re facing opposite to the direction the ladies exited. Women (Farrell) one way, the Eternal Feminine the other.

The first woman has to be liquid (Balanchine set this part on Violette Verdy), and Larissa Ponomarenko, with an attentive Nelson Madrigal as her partner, was. Opening night, Yury Yanowsky and Lorna Feijóo looked ill-matched and ill at ease; partnered with Madrigal on Sunday, Feijóo caught the flow of the music better. Dancing with Carlos Molina Thursday and Lorin Mathis Sunday, Erica Cornejo was rapturous in the Mimi Paul second-lady role. The Boston Ballet Orchestra under Jonathan McPhee made palpable the contrast between oboes and horns, hunted and hunter, women and men.

Topics

Topics:

Dance

, Entertainment, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edward Villella, More  , Entertainment, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edward Villella, San Francisco Ballet, Suzanne Farrell, Laura Jacobs, Maurice Maeterlinck, wang theatre, wang theatre, Jewels, Less

, Entertainment, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edward Villella, San Francisco Ballet, Suzanne Farrell, Laura Jacobs, Maurice Maeterlinck, wang theatre, wang theatre, Jewels, Less