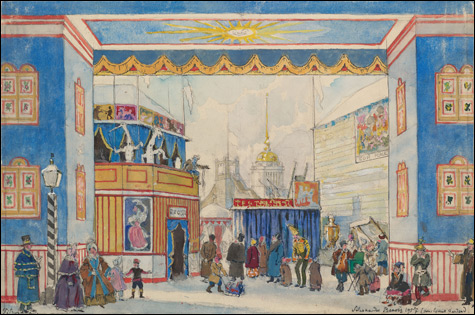

PETRUSHKA'S TOWN FAIR The 1911 Fokine/Benois/Stravinsky ballet was an evocation of old Russia. |

Of the nearly 70 ballets that made up the repertory of Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, only a few inhabit our stages today. But the Diaghilev adventure still inspires legions of choreographers, antiquarians, archivists, scholars, and gossips. Last week the Harvard Theatre Collection at Houghton Library led off a season of Boston festivities commemorating the legendary company that gave its first performances in Paris 100 years ago.

Organized by Theatre Collection curator Frederick Woodbridge Wilson, "Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, 1909–1929 — Twenty Years That Changed the World of Art" featured a sumptuous exhibit of letters, manuscripts, programs, scenic and costume designs, musical scores, photographs, and artifacts from the Collection's impressive holdings. The show continues at Pusey Library through August. What a flamboyant, mind-grabbing array of images!

With remarkable skill and an uncanny instinct for the new, Diaghilev brought successive waves of modernist painters, poets, composers, and choreographers together to galvanize the ballet stage. Even a cursory look at the exhibit's wealth of materials reveals the creative ferment of an era when art in Europe was emerging from the 19th century to engage with the modern world: the nostalgic impressions of Alexandre Benois (Le Pavillon d'Armide, Petrushka), the exoticism of Léon Bakst (Sheherazade, Firebird), the Cubist fragmentations of Picasso and Satie (Parade), the Slavic rituals of Stravinsky, Nijinsky, and Nijinska (Le Sacre du Printemps, Les Noces), the constructivist ballets, the narrative ballets, the party ballets, the classical revivals, and the beginnings of Neo-Classicism.

You couldn't say there was ever a Diaghilev "style," though scholars keep trying to tease one out. Perhaps Diaghilev needed to reinvent himself over and over, as an impresario who was intimately tuned into the avant-garde and able to enlist the trendiest trendsetters as collaborators. Perhaps he was motivated by nothing more noble than the marketing and money-raising that would keep the company solvent. Perhaps he had old scores to settle or new ideals to bring to the world. These possibilities and more were explored by a diverse roster of musicologists, historians, theorists, curators, collectors, and performance scholars during a three-day symposium at the New College Theatre, but Diaghilev remains a mysterious figure, as shadowy and subject to interpretation, in fact, as the ballets themselves.

We know the Ballets Russes from the archives and artifacts, from word-of-mouth accounts and handed-down revivals that linger in ballet-company repertories, like Les Sylphides (Michel Fokine, 1909). In the closing session of the symposium we finally heard a panel of active ballet practitioners, critics, and presenters. They seemed to agree that the Ballets Russes will survive — in the mind. Diaghilev's artistic legacy may be not the ballets themselves but their potential to serve as inspiration for the artists of our time. Virtually no assessment was made during the symposium of restagings, reconstructions, and revivals of the original works as they're presented in current repertory.

The inspirational stream is far from tapped out, as demonstrated by three of its products that were shown during the week. On Thursday afternoon, Basil Twist brought his New York–based company of young puppeteers for a demonstration and discussion of his 2001 Petrushka. Puppets are some of the oldest and most universal figures in performance history, and the characters of Petrushka (as Pierrot or Pedrolino), his ballerina (a/k/a Columbine), and the Moor have been staples of Russian folklore and commedia dell'arte for centuries.