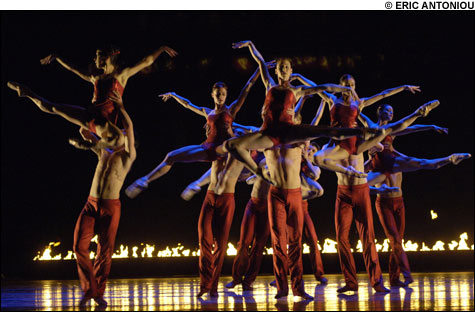

LE SACRE DU PRINTEMPS: Lighting up the Wang in Jorma’s Elo new ballet to Stravinsky’s score. |

“Burning down the house” is a metaphor, but at the Wang Theatre last weekend, the Boston Fire Department was on hand to ensure that it remained one. All the same, audiences had a hot time at Boston Ballet’s season finale, where, in Jorma Elo’s incendiary Le Sacre du Printemps, it wasn’t just the flames flickering in the background that lit up the stage.

It was fitting that Boston Ballet should bid farewell to the Wang — it will stage all its productions at the Opera House next season — with “Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes Centennial Celebration.” Serge Diaghilev’s company kicked ballet into the 20th century, with its avant-garde composers (Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Prokofiev) and choreographers (Fokine, Nijinsky, Nijinska, Balanchine) and designers (Benois, Bakst, Picasso) and dancers (Nijinsky, Karsavina, Lifar, Danilova). Put Schéhérazade, Firebird, Petrouchka, Les Noces, or Apollo up against most contemporary choreography and it’s the newer stuff that seems dated. In this trio of Ballets Russes originals — Balanchine’s The Prodigal Son (1929), Fokine’s Le Spectre de la Rose (1911), and Nijinsky’s Afternoon of a Faun (1912) — plus resident choreographer Elo’s version of the most famous Ballets Russes piece of all, Boston Ballet looks forward as well as back.

These four works are also modern in their focus on the isolation of the individual. Nineteenth-century story ballets are about community and romance; only Giselle and La Sylphide end in death and desolation. Balanchine’s Prodigal is fleeced by the Goons, seduced by the Siren, and deserted by his two friends; when at the end he crawls back into the embrace of his father, it’s as if he were re-entering the womb. In Le Spectre de laRose, a young woman returns home from a ball bearing a rose (that an admirer has given her?) and falls asleep in an armchair, whereupon she’s visited by the title apparition, the man of her dreams, with whom she dances — but was it all a dream? At the end, she’s alone, clutching her rose. Afternoon of a Faun opens with our hero in solitary splendor atop a rock, playing his flute and munching on grapes — until some nymphs troop by on their way to bathe in the lake. He cavorts briefly with one of them; she drops a silken scarf before slipping away (he’s looking in the opposite direction), and he takes it back to his perch, stretches it out, lies on it, masturbates. In Nijinsky’s Sacre, a virgin is chosen from the community to be sacrificed to the earth. Elo’s ballet takes up the same theme.