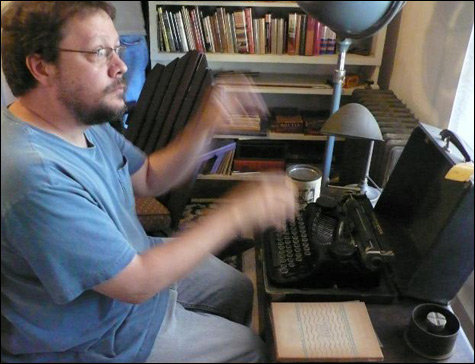

ZEN FOG: Pendarvis’s style is pre–Barry Hannah, post–George Saunders — satirically chatty, with a High Mannerist naïveté. |

| Shut Up, Ugly | By Jack Pendarvis | MacAdam/Cage | 254 pages | $14 |

John Gardner, the great teacher and novelist who wrote approximately 413 books before annihilating himself on a motorcycle in 1982, was very big on vocabulary. "The good writer," he declared in The Art of Fiction, "is likely to know and use — or find out and use — the words for common architectural features, like 'lintel,' 'newel post,' 'corbelling,' 'abutment,' and the concrete or stone 'hems' alongside the steps leading up into churches or public buildings." Writers should also be conversant, according to Gardner, in "the names of carpenter's or plumber's tools . . . and the names of common household items, including those we do not usually hear named, often as we use them, such as 'pinch-clippers.' "Pinch-clippers, eh? Oh well. These days nobody (and especially not a writer) remembers the name of anything — that's why we have Google. The only flower I can identify with any confidence is a daffodil, and the only make of car I am certain of recognizing is a Rolls-Royce. Once I regarded this incapacity in the light of a private mental defect; now I understand that it makes me a representative modern man. Jack Pendarvis, I suspect, is similarly gifted. Here's Burns, the protagonist of his new novel, Shut Up, Ugly, going about his business: "On the way he passed a church. He saw some birds — he didn't know what kind; they were brown — pecking at something — what do birds peck at? seeds? — on the lawn."

Burns, jobless and nearly homeless, stunned by a recent falling-out with his friend Harris (his only friend, it appears), ambles through Pendarvis's novel in a species of Zen fog, uninterested in distinctions, opinions, or classifications. He is "looking forward to not having a personality anymore." He meets girls, in a manner of speaking, and does stuff. On the back of Shut Up, Ugly, it says that he's some sort of ironic detective, but you might (as I did) forget about this until page 155, when he makes a phone call and announces, rather dubiously, "There's been a break in the case."

What is Burns good for? That's the question. It's clear he's not good at anything. And yet he has an attraction for us. His state of spiritual concussion, caused perhaps by unacknowledged grief over his sudden severance from Harris, is somehow our own. Or my own. Pendarvis has a style I would describe as pre-Barry Hannah, post-George Saunders, satirically chatty, with that kind of High Mannerist naïveté. His characters babble in slow motion — thus, " 'I'm in a charitable mood,' said Mrs. Melon. 'Can you open that freezer door for me? It's so high up, and the suction is strong.' " A little of this goes a long way, but that's the point: Burns, poor reduced Burns, is operating out of a tiny stub of Mind, right at the back of his head, and he has to make it do all the work. Baffled by this, menaced by that, he builds to a final non-revelation: "All civilization really requires of you is for some random words to come out of your mouth."