POSSESSED? A glass globe in Zugunruhe. |

Rachel Berwick's art is concerned with conjuring ghosts — in particular the spirits of creatures or peoples near extinction or already died out. Her conceptual art installations — like her new piece Zugunruhe at Brown University's Bell Gallery (64 College Street, Providence, through February 14) — hover somewhere between monument and séance and Jurassic Park-style resurrections of the disappeared.

"There's a common theme that runs through all of my work," Berwick tells me, "and it is working primarily with the notion of loss and our desire to recover that which is lost. And then following that through, the impossibility of that, but the importance of the attempt to recover even in the case of probable failure."

In one past work, Berwick, who chairs RISD's glass department and resides in Killingworth, Connecticut, has produced 3D renderings of a Tasmanian tiger based on a brief film of one of the critters before the species went extinct. Another time, she taught parrots the language of an extinct Venezuelan native people, a language said to have only survived to be recorded by a German naturalist in 1799 because when a neighboring tribe's raid wiped out its last human speakers, the attackers took their victims' parrots, which remembered their language.

Zugunruhe is one of the finest things she has done. It picks up on themes she first addressed in A Vanishing: Martha (2003-05), which was a sort of 3D grid of passenger pigeons cast in orange copal. It represented the species' reduction — particularly by human hunting — down to one bird, Martha, who died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.

Zugunruhe is an ornithological term describing nighttime restlessness in birds getting ready to migrate. The piece's subject is that departure as a metaphor for the vanishing of the enormous flocks of passenger pigeons, a force of nature hardly imaginable today.

The first room displays a rare copy of naturalist John James Audubon's 1840 book Birds of America, opened five feet wide to actual-sized illustrations of a pair of passenger pigeons. A gray and tan female reaches her beak down into the blue and orange male's beak to receive regurgitated food.

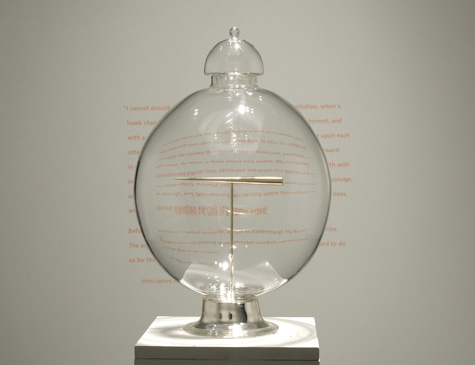

On a pedestal in the second room stands a glass globe with a little arrow inside that rotates erratically, pointing around the room as if possessed. The walls are printed with texts by 19th-century naturalists or hunters recounting encounters with passenger pigeons. Simon Pokagon of the Pokagon tribe describes a "gurgling, rumbling sound" like "an army of horses laden with sleigh bells." Or maybe it's "distant thunder." Then he sees "moving toward me in an unbroken front millions of pigeons . . . They passed like a cloud through the branches of the high trees, through the underbrush and over the ground, apparently overturning every leaf." Alexander Wilson recalls a flock taking at least five hours to pass overhead. Audubon writes, "The light of the noonday was obscured as by an eclipse." These accounts instill a feeling of impending doom, because we know how the story ends.

BEAUTIFUL AND SURREAL The installation resonates with Berwick's thinking. |

The last gallery is a large dark room with a tall seven-sided glass case in the center. Spotlit inside is a stumpy leafless tree standing in the middle of a muddy lawn. Hundreds of passenger pigeons sit on the branches. They're cast in copal, a sort of immature amber ("It's about a million years old, as opposed to three million years old," Berwick says), the color of frozen orange Crush.