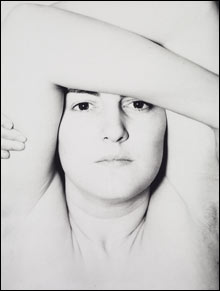

ELEANOR (circa 1947) Vastly influential, Callahan expanded the art world's very definition of photography. |

What I want to do — what most photographers want to do — is write Harry Callahan a love letter. At the very least, he deserves an elaborate thank-you note for innovating or validating 80 percent of the successful photographs we ever took. Yes, Callahan's influence — direct and indirect — has been that encompassing, that universal. And yet the MFA has managed to encapsulate his imprint on the photo-art world in a tiny exhibit (roughly 40 prints), "Harry Callahan: American Photographer," that's on display in the Herb Ritts Gallery through July 3, 2010.Through his lifelong devotion to "personal" photography, the Detroit-born and virtually self-taught Callahan explored the limits of the medium and its technology so thoroughly that, from the late 1930s through his retirement (in 1977, when he left a teaching post at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he'd founded and for many years chaired the photography department), he produced what amounts to a primer of 20th-century photo-art motifs and standards. His long tenure at RISD, which began in 1961, inspired a double-generation-plus of photographers, many from New England, who owe their diverse bodies of work to his relentless experimentation.

Up here at MIT, photo-pantheon mainstay Minor White, who from 1965 to 1974 headed that school's legendary photography department (which Callahan had declined to helm), cultivated a similar minion of devotees. But White's offspring, brilliant though many have been, were often confined by their master's block-of-detail vision, whereas Callahan's were open to anything from street-photography grab shots to multiple-exposure collages to revealing semi-formal portraits of their friends.

Callahan's talent was organic. He took up the camera in 1938, at age 25. Inspired by an encounter with Ansel Adams, he forsook — or, more accurately, ignored — the evolving genre's early ambitions to imitate fine-art painting and went whichever way the camera led him. By 1946, he'd been invited to teach at Chicago's Institute of Design. Two years later, he had work shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was hanging around with Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen.

Although he limited his subjects to architecture, landscapes, street candids, and, most famously, his wife, Eleanor Knapp, the scope of Callahan's photography seems infinite. Pushing every aspect of shooting, composition, and darkroom manipulation just to see what would happen resulted in techniques, not gimmicks. That obsession — along with an ingenuous knack for combining elements of visual geometry, contextual lighting, and intimate portraiture — expanded the art world's very definition of photography.

According to former RISD protégés, who spoke informally to the press at the MFA's preview, Callahan's days were routine. He'd shoot all morning, drink his lunch at a Providence saloon (where he proudly claimed to be the only regular who'd had a one-man show at MOMA), and then teach before finishing his workday in the darkroom.

His relentless program of trial and variation produced not the expected flood of photographs but a selective body of perfected results — which is why this small display at the MFA says so much. The exhibit, deftly curated by the MFA's Anne Havinga and Emily Voelker, will entertain casual visitors, but it could approach epiphany for photographers. Unfortunately for that professional audience, the show — packaged as art, not example — omits the technical data and individual print histories that would make the tiny collection a more satisfying history lesson. But even serious amateur shooters will spot reflections of their own work in Callahan's. His unconscious impact on our collective vision was that strong.

CLIF GARBODEN | cgarboden@gmail.com