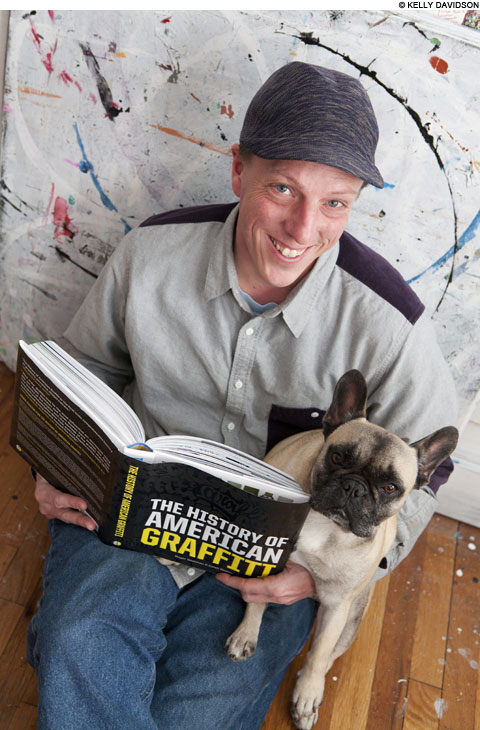

HISTORY LESSONS Neelon and Gastman’s work stakes a major claim at being the definitive history of the art form, with hundreds of snapshots of breathtaking tags and the people who made them. |

'TAKI 183' SPAWNS PEN PALS, announced the headline in the July 21, 1971, New York Times. It told the story of a 17-year-old Greek kid named Demetrius (Taki is a traditional nickname) living on 183rd Street in Manhattan who had taken to scrawling "Taki 183" in marker on subway cars and stations between his home in Washington Heights and his high school in Midtown, on lampposts and walls while on his job delivering cosmetics to Upper East Side and Gramercy Park homes, and really all over New York City. His tagging made him famous among his peers, inspiring many others to take up markers, and infamous among civic leaders, who struggled to control the vandalism."I just did it everywhere I went," he told the Times then. "I still do, though not as much. You don't do it for the girls; they don't seem to care. You do it for yourself. You don't go after it to be elected president."

>> PHOTO SLIDESHOW:Photos: American History of Graffiti <<

Forty years on, Taki is honored as one of graffiti's founding fathers in the new book The History of American Graffiti (Harper Design, $40) by Caleb Neelon of Cambridge, whose own paintings will be exhibited at the DeCordova Museum in Lincoln in June, and Roger Gastman of Los Angeles, a co-curator of the April exhibit "Art in the Streets" at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. In a proliferating library of graffiti books, the 410-page tome stakes a major claim at being the definitive history of the art form. And it's astonishingly illustrated by hundreds of snapshots, mostly by the artists themselves. "Nearly every single artwork featured in this book," Neelon and Gastman note, "has been destroyed."

QUINCY MARKED IT

People have been scrawling names and pictures on stuff forever. Neelon and Gastman, for example, highlight "Kilroy Was Here," which began with James Kilroy, who worked at the Quincy shipyard during World War II. He would write his mark on boats to confirm that various tasks were complete. Then servicemen who rode the ships to war scrawled it everywhere they fought, like a banner of the liberators.

But graffiti, the phenomenon we know today, began with teens magic-markering their names across Philadelphia and then New York in the late '60s. What was new was magnitude — writing your name everywhere. It was a game of one-upmanship, driving taggers to do more, do it bigger, do it in more daring locales. And it thrived in the chaos of broke New York. "All this is a pretty amazing thing when you're talking about 15-year-olds making this," says Neelon, "furtively, in places they're not supposed to be, with materials that are not supposed to be art materials."