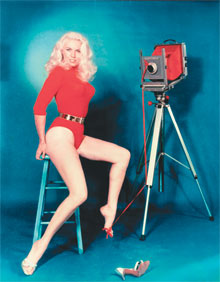

Bunny Yeager, self-portrait, 1960s |

Pin-up photography has served so many purposes — outlet for male desire; outlet for feminist ire; retro kitsch emblem — that it has barely been talked about as photography. To be fair, there is something a little perverse about that approach. It's a very dull person who sees photographer Bunny Yeager's shots of Bettie Page, or of herself, and first thinks of lighting or composition. Yeager herself seemed to strike a balance, issuing large-format paperbacks of her pin-up shots in 75- and 95-cent editions with titles like Bunny Yeager's ABCs of Figure Photography. The books combined Yeager's work with basic, common-sense advice on how to use props, settings, etc., for the amateur shutterbug: "Start with yards of material to create a feeling of luxury and abundance. Stretch it, swirl it, crinkle it, plump it, put a pillow under it."

>> SLIDESHOW: Bunny Yeager's darkroom <<

That advice says a lot about the tenor of the work found in the new Rizzoli coffee-table volume, Bunny Yeager's Darkroom: Pin-up Photography's Golden Era. Flipping through the work contained here, some of it previously unpublished, I found it hard to separate the friendly, inviting nature of the women Yeager shot from the settings she chose. It's an easy connection to make with the beach shots. Yeager was based in Miami and frequently worked on shoots outdoors (sometimes with her buddy Sammy Davis Jr.). As Yeager remembers and other writers have confirmed, Bettie Page had a complete naturalness about nudity (which Yeager distinguished from being naked); the sand and sea only added to that feeling of sensual luxuriance she exuded. In one two-page shot, a radiant Page stands to the right of the frame, a black peignoir blowing behind her. That Yeager gives most of the frame over to the garment, rippling out to the left like a flag, conveys the ocean breeze on Page's skin, and suggests that nature itself is freeing her from even this minor incumbrance.

But I found myself paying more attention to the clean, uncluttered '60s-modern interiors (many, I believe, in Yeager's own residence). This is not some Mad Men bit of nostalgia (the costuming and art direction of that show reducing everything else to the level of dioramas at the Museum of Natural History). Together with the models, the indoor settings here seem to suggest what was always beneath the sexual appeal of these photos: the promise of an attainable good life of ease and casual elegance. Sleek couches, textured draperies, geometric tables with slim legs, the furnishings spare but not cold — these were settings you could live in as well as admire, and where you could, presumably, enjoy the pleasures these women promised.

If there's one detail of these interiors that seems crucial, it's the venetian blinds. They remain open, letting in the sun, suggesting that sex may be veiled but not hidden away.

The other crucial detail is the title of Yeager's most famous book, How I Photograph Myself. She is a frequent model here, always commanding attention, but perhaps more believable looking stern than trying out a smiling come-on. Yeager is telling us she's in charge. Yet not a dictatorial figure, making a place for these women to present their own definitions of themselves. That Yeager (now 82 and still living in Miami) remains the best-known and best-loved of all pin-up photographers is a paradox all the dismissive reductions of glamour photography have yet to deal with: at the center of a genre which has provided so much pleasure to men lies a female eye.

BUNNY YEAGER'S DARKROOM: PIN-UP PHOTOGRAPHY'S GOLDEN ERA | By Petra Mason :: Foreword by Dita Von Teese | Rizzoli, 256 Pages, $60.