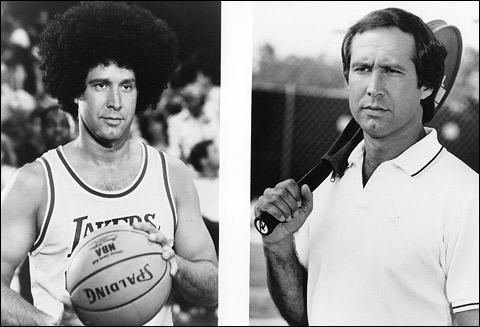

SIX-NINE WITH THE AFRO: Twenty years before Internet video, Chevy Chase served up a series of “Funny or Die” shorts with Fletch. |

This holiday weekend marks the 25th anniversary of Fletch, the uneven but wildly enduring 1985 Chevy Chase comedy about a wisecracking reporter embroiled in a potboiler mystery. This means that a certain subset of white dudes who came of age in the mid ’80s have been talking about how it’s all ball bearings and telling waitpersons to put their steak sandwiches on the Underhills’ tab for longer than Lindsay Lohan has been alive.

And they’re showing no sign of abating:

Fletch has not one but two Facebook fan pages, and the Internet is rife with

Fletch-related paraphernalia, especially T-shirts and hard to find jerseys that pay homage to Irwin Fletcher’s obsession with the LA Lakers. Then, of course, there is the long list of noted comedic actors who have been named heir to the

Fletch throne in any number of never-made sequels and attempted reboots. (The latest candidate is Zach Galifianakis.)

So how did a modestly funny comic-noir adaptation grow into such a durable cultural artifact? It’s partly due to the fact that the film works as much as a collection of disembodied one-liners as it does a unified whole. Segments of the population appear to have memorized every word in the script, and, in certain circles, quoting it out of context is still a badge of comedic honor.

One doesn’t actually have to watch the movie in its entirety to appreciate the moments of comedic brilliance. In fact, in some ways the film is better when taken as a series of bite-sized sketches stitched together by a threadbare mystery plot. Twenty years before the widespread acceptance of Internet video, Fletch was a series of “Funny or Die” shorts.

Almost all of this owes to the improvisational skills of Chase, who took Gregory McDonald’s laconic character off the novel page and turned him into a detached smart-ass who had a penchant for Dada-esque surrealism and screwball pratfalls. (It’s impossible to envision anybody other than Chase in the lead role, though also considered were, bafflingly, both Burt Reynolds and Mick Jagger.)

While parts of the persona made brief appearances in Chase’s earlier work (most notably Foul Play and Caddyshack), Fletch allowed him to fully birth the ironic hero whose weapon is his wit. He might as well have been filming a long-form monologue on a soundstage full of mannequins. Indeed, as New York Post film critic Kyle Smith notes, Fletch is really two unrelated films.

“One is a wheezy mid-’80s made-for-TV caliber mystery with a goofy Harold Faltermeyer score — this is the movie that everyone but Chevy Chase is in,” says Smith. “But the other movie, the Chevy Chase movie, is a classic because the character is one of the great cinematic wiseasses of all time, right up there with William Holden in Stalag 17 and Bob Hope. Of course, Fletch represented an advance that was informed by the absurdist humor that so appealed to the ’80s audience raised on Monty Python, Steve Martin, and David Letterman.”