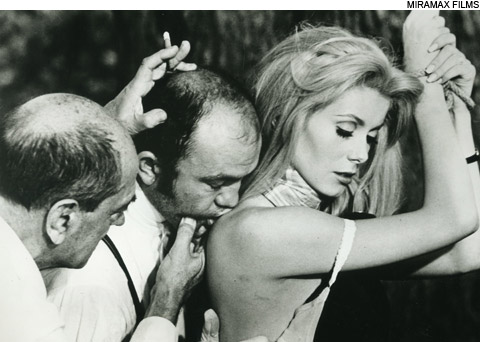

THE MUD! Buñuel demonstrates his hands-on directing style during the making of In Belle de Jour, with Catherine Deneuve. |

Openly, contentedly delighted with how our own dreams can appall us, and how close movies are to that appalling dreaminess, — the subject of an extensive survey at the HFA this month — may have been the greatest filmmaker of the medium's first century. Had any filmmaker realized so acutely the unconscious torque inherent in cinema? Certainly among the 12 or so unassailable masters of the medium, he is the wittiest, the most philosophically imaginative, and the most formally unceremonious. His career stretched nearly 50 years, culminating amid what could be thought of as the death throes of international art cinema; his last masterpiece That Obscure Object of Desire (1977; June 18 @ 9 pm) hitting the open air the same year Star Wars forever wrecked the popular market and turned moviegoing into a experience of childish spinal emergency. He released his grasp on us at just about the right time — his serenely wicked, tipsy-Voltairean sensibility never had to do battle with the powers of Reagan-era idiocy.

It's just as well: from the beginning Buñuel stood outside of fashion, and just as his flirtation with Surrealist dogma quickly became an individual vision more concerned with conscious human folly than with unconsciousness liberation, Buñuel always required the audience to acclimate to his worldview, never the reverse. It helps that it's a worldview fraught with contradictions, defined by patience and scorn, peopled with pious sinners and debauched saints, visually spartan and yet spasming with bouts of the irrational. This was Luis's world — welcome to it.

Newbies to Buñuel's cataract of mysterious fun may be mystified at first — where are the pyrotechnics, the daring rigor? Let's say this: Buñuel is among the very few cinema giants you could never accuse of pretension (Renoir, Ozu, and Bresson are the other three), his sense of irreverence remains a Swiftian glory of a kind too rarely acknowledged as "art," and his surgeon-like evaluation of his audience's desires and impulses is rivaled only by Hitchcock.

Still, you don't need to be quite converted to Buñuelism to fathom the magic of his debut, Un chien Andalou (1928; June 17 @ 7 pm), the seminal Surrealist hand grenade conceived and executed with Salvador Dalí that is far more than just 16 fuck-you minutes of incendiary narrative hijinks, dead donkeys, misplaced armpit hair, ants, cocktail-shaker doorbells, and severed hands. It's more, in fact, than a movie — it's a cultural explosion that's still sending off shockwaves and flinging shrapnel, seeding our world with poisonous ideas about the joie of irrationality.

This wager was doubled-down with L'Age d'Or (1930; June @ 7 pm), shot sans an impatient Dalí, and merely the most troublesome film ever made, aggressively blasting taboos against sexual lust, fetishism, sadism, coprophilia, blasphemy, anti-nationalism, anti-clericism — you name it. In those hot-blooded days of yore, the film's affront was such that right-wing groups mobilized their newspapers' readers to physically decimate the Paris theater in which it played (slashing Dalí and Ernst paintings hanging in the lobby as they went). Two days later, police shut the movie down for good. Running famously from an educational documentary about scorpions to the climactic revelation of a beardless, orgy-exhausted Christ, Buñuel's devilish gob-in-the-eye still owns the throne as subversive culture's wickedest anthem film.