OPERA IN SOMERVILLE! Even with its misplaced ’70s-disco setting, this was a Falstaff worth cheering. |

In 1992, Somerville novelist Jonathan Strong published Secret Words, a wonderful book that had one major implausibility — it centered around an opera company that was putting on a Verdi opera in Somerville! But Boston Opera Collaborative has now proved that truth is as strange as fiction, staging a great Verdi opera at the Somerville Theatre (through July 24): his final masterpiece, Falstaff, composed as he was approaching 90 (and 53 years after his only other comedy) — its deliriously effervescent score both wise and the essence of youth.

BOC is, in its own words, "a non-profit membership organization dedicated to providing opportunities for emerging artists." Its members share in both the artistic and administrative work. Now in its sixth year, it has created a stir. At least on the basis of Falstaff, the group is doing most things right. Impressive singing actors fill the major roles and a superb up-and-coming conductor, Mischa Santora, leads 23 refined players in the newly renovated orchestra pit. Not every detail of Verdi's most complex ensembles was strictly in place, but everyone seemed to be having a great time, which was infectious.

Frustratingly dim supertitles aside, my primary reservation concerns Heidi Lauren Duke's staging, despite how much fun I had. Arrigo Boito, Verdi's great librettist, created something profoundly original from what he assembled combining Shakespeare's Henry IV plays and its sequel, The Merry Wives of Windsor. We get the impecunious, fat, horny Sir John Falstaff, who thinks he can seduce wealthy Windsor ladies. His absurdity stirs them to plot his comeuppance. With its inescapable historical setting, this doesn't seem an opera that could survive updating.

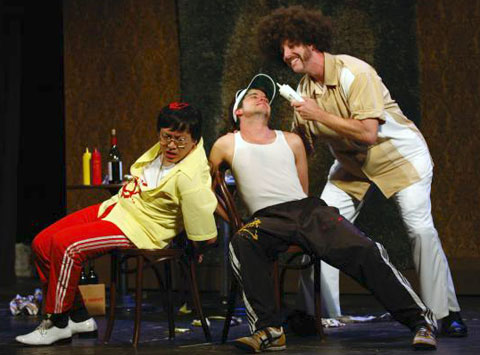

But Drake sets it in the disco '70s, with Falstaff a bloated Travolta wannabe and all the characters down a step or two on the social ladder. It was funny, but much of Verdi's poignance, and Sir John's underlying aristocratic elegance, are missing. One exquisite moment comes when Falstaff, in the midst of his attempted tryst with Alice Ford, loses himself in a reminiscence of his youth, so thin and supple he could dart through a ring. Drake has Falstaff stick a finger back and forth through the thumb-and-forefinger circle of his other hand. The audience roared, but it destroyed what Verdi and Boito intended. During Falstaff's famous riff on the meaninglessness of honor ("Can it fill your belly? No!"), Drake has him handcuff his henchmen Bardolph and Pistol to a chair and squirt mustard and catsup over them (the audience audibly gagged). These shticks upstage both words and music.

Still, baritone Kevin Kees, with his exploding Afro wig, obvious padding, and strong, full-bodied, resonant, characterful voice, manages to create a convincing, larger-than-life Falstaff. Soprano Lindsay Conrad is a vivacious, teasing Alice Ford, with a powerful, bright, three-dimensional tone. Her voice soared over the orchestra in the great arching melody Verdi gives her.

Tenor Nicholas Hebert, the only major singer in BOC's double cast to appear in all performances, is a skillfully comedic, vocally secure Bardolph. Jacob A. Cooper makes a sturdy, disturbingly jealous Ford (one cracked high note came out of nowhere). Soprano Megan Stapleton (Nannetta, the Fords' daughter) is enchanting in her third-act aria. Mezzo-soprano Brooke Larimer, Mistress Quickly in toreador pants, boa, and hoop earrings, proves she can sing and chew gum at the same time. In smaller roles, Amanda Robie, Isaac Yager, James Liu, and Brendan P. Buckley are all commendable. If BOC's ambitions deserve our support, this spirited production earns it.