Johannes Chrisostomas Wolfgang Gottlieb (Amadé) Mozart was born 250 years ago last Friday, January 27. He lived just under 36 years; fortunately, he got off to an early start and produced some of Western music’s most ravishing and profound works, compositions of earthy humanity and unearthly spirituality, works of radical simplicity and mind-bending, heart-expanding complexity. In celebration of this landmark anniversary, we’ll be hearing a lot of Mozart — symphonies and concertos, chamber music and operas. We could have worse years.

Johannes Chrisostomas Wolfgang Gottlieb (Amadé) Mozart was born 250 years ago last Friday, January 27. He lived just under 36 years; fortunately, he got off to an early start and produced some of Western music’s most ravishing and profound works, compositions of earthy humanity and unearthly spirituality, works of radical simplicity and mind-bending, heart-expanding complexity. In celebration of this landmark anniversary, we’ll be hearing a lot of Mozart — symphonies and concertos, chamber music and operas. We could have worse years.

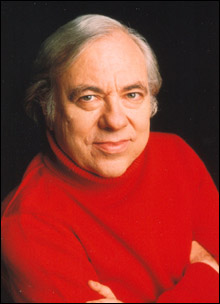

Emmanuel Music, the organization responsible — under the more-than-three-decade directorship of pianist and conductor Craig Smith — for some of Boston’s greatest Mozart performances, began its Mozart celebration on the birthdate itself. Pianist Russell Sherman is perhaps Emmanuel’s most frequent guest in its long history of Mozart-birthday tributes (his recording of Mozart’s C-minor and D-minor Piano Concertos, with Smith and the Emmanuel Orchestra, is a magnificent testament to their collaboration), and he returned to launch a major Mozart project — the performance and recording of five concerts that will include all of Mozart’s piano sonatas (the remaining concerts are February 25, March 11, April 22, and May 6) plus a concert version of Die Zauberflöte (April 28 and 30).

Let’s get the quibbles over with. Emmanuel Church isn’t the most intimate concert venue, and its uneven acoustics are a hurdle for both audiences and performers. Sitting about halfway back, I felt too far away from the piano, and in the impetuous, even peremptory rush of the fast movements of Sherman’s first three sonatas (K.280, in F; K.311, in D; K.333, in B-flat), details were getting lost. Friends sitting closer loved Sherman’s fleetness and delicacy but were distracted by the clanking of heating pipes (which I couldn’t hear at all). I’m one of the few people I know who actually enjoys the speed of Glenn Gould’s eccentric Mozart sonata recordings (Gould said he didn’t like Mozart’s sonatas); he makes the sonatas sound like silent-movie music, Keystone Kops chases. Sherman clearly loves this music and seemed swept away by it, revealing in passing some startling harmonic clashes in the inner voices. The finales were mercurial, sometimes teasing. In the slow movements, Sherman was also searching, prefiguring in his playing of the Adagio of the F-major Sonata the exquisite slow movement of Mozart’s A-major Piano Concerto, K.488 (which Richard Goode played with Bernard Haitink and the Boston Symphony Orchestra that same weekend — more about which later).

A week before, pianist David Deveau and friends had played a fascinating and complex reduction of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto (partly by Beethoven) with five stellar string players. At Emmanuel, Sherman was joined by the Lydian String Quartet and bassist Gregory Koeller for Mozart’s sublime Piano Concerto No. 12 in A, K.414. Beautiful as Deveau’s Beethoven was, it never convinced me it was meant to be a chamber piece — the Fourth is just too big. But Mozart’s subtle, intimate, inward-looking concerto works just fine with a piano and one string to a part. The playing on all parts was a marvel of warmth, tenderness, and character. Four years before Le nozze di Figaro you could hear Figaro’s capering comedy, and the sadness that comedy hides. Sherman is always thinking, you hear his mind working, which means that his playing is always alive, in the moment. He hears fanfares, hymns (that heavenly Andante), meditations interrupting the high jinks. And so do you.