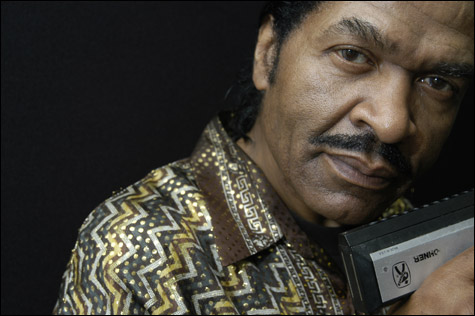

PERENNIAL: Rush has been chalking up soul-blues hits since he cut the risqué rump shaker “Chicken Heads” in 1971. |

Bluesman Bobby Rush is notorious for sassy R-rated stage shows full of bushy double entendres and buttocks-twitching hoochie dancers that have made him king of the chitlin circuit. But he’s also a serious musician who, in parallel with fellow harmonica ace the late Junior Wells, developed the blues-funk sound. And unlike his pals in the formative Chicago blues scene of the 1950s and ’60s, who included Little Walter, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Luther Allison, and Freddie King, Rush — who’s nearing 74 — is not only alive but thriving. He’s even found a new mission: pumping fresh blood into his earliest musical roots with his just-released Raw, his debut as a solo performer, on his own Deep Rush label.

When Rush starred with B.B. King in “The Road to Memphis,” part of Martin Scorsese’s The Blues PBS series in 2003, he reached more white listeners than ever in his 60-year career. Nonetheless, he’s been chalking up soul-blues hits since he cut the risqué rump shaker “Chicken Heads” in 1971. He has more than 100 albums on his résumé, all mostly devoured by an ardent, albeit now aging, Southern-rooted African-American fan base.

“I’ve got good reasons for making Raw,” he explains over the phone from Chicago. (His home since the early ’80s, however, has been Jackson, Mississippi.) “Some of them are practical. I started off in little juke joints, but when I’m carrying my 10- or 12-piece band, I can’t afford to play 200- or 300-seat clubs. It’s so expensive to tour a big group these days that only festivals and casinos and venues like that can afford to cover my costs and let me make a little profit. Playing by myself, it’s cheaper to travel, and I can charge less, so the little places can have me and I can still make about the same money personally. So it’s good for the little clubs and good for me.

“Another reason is that I love this music. It’s really at the heart and soul of what I do. My daddy was a preacher, but he also played and loved the blues, and I inherited that from him.”

Throughout Raw, Rush’s exuberance in bending themes from the Sonny Boy Williamson and Howlin’ Wolf catalogues into Rush tunes like “School Girl” and “Howlin’ Wolf” booms through his keening vocals and bleach-boned guitar picking, all of which is punctuated by singing blasts of harmonica virtuosity. But in “How Long” he takes a serious turn, examining the indelible stain slavery left on African-American culture. “That’s a theme I hope young black people can relate to, because so many of them want nothing to do with the blues and songs about ‘My woman done left me’ and how much whiskey somebody drank. I hope that if young black musicians see a black artist who runs his own successful business affairs like I do playing real, old-school, back-to-the-roots blues, more of them might start playing it. I want to inspire them to play blues the old way, when it was truly black music. Today, a lot of young black musicians who do play blues are trying to sound like white musicians who are trying to sound like black musicians, instead of honoring their own heritage.”