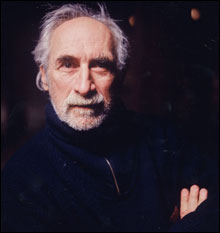

I’ve heard a lot of music in the past couple of weeks — concerts by two major symphony orchestras, with two major young violinists, a hot new-music group, and two opera productions. One high point was the piano recital in the Boston Conservatory’s Piano Masters Series a week ago Tuesday by American maverick Frederic Rzewski (pronounced “zhefskee”), who studied with such polar opposite composers as austere Roger Sessions and appealing Virgil Thomson, and whose best known piece is probably his near-hour-long series of piano variations on a Chilean theme, The People United Will Never Be Defeated (1975).

I’ve heard a lot of music in the past couple of weeks — concerts by two major symphony orchestras, with two major young violinists, a hot new-music group, and two opera productions. One high point was the piano recital in the Boston Conservatory’s Piano Masters Series a week ago Tuesday by American maverick Frederic Rzewski (pronounced “zhefskee”), who studied with such polar opposite composers as austere Roger Sessions and appealing Virgil Thomson, and whose best known piece is probably his near-hour-long series of piano variations on a Chilean theme, The People United Will Never Be Defeated (1975).

Rzewski started with Four Pieces (1977), a sequel to The People United that suggests without quoting Chilean folk music, and the more recent Cadenza (2003), a dazzling, improvisatory 13-minute fantasy on themes from Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto intended to be an actual cadenza for a performance of the Beethoven. (“I got carried away!”, Rzewski, who embodies down-to-earth, acknowledged — he also admitted that he remains puzzled by which of three possible places for improvisation in the concerto Cadenza could go and is still uncertain about how to end it.)

After some discussion with the audience about whether an intermission was desirable (the conclusion was no), Rzewski launched into De Profundis (1992), an extraordinary “melodrama” in which he accompanies himself reading seven substantial excerpts from Oscar Wilde’s book about his imprisonment for sodomy after losing a lawsuit that accused the Marquis of Queensbury of slander. Rzewski read with poignant intensity, as articulate in diction as in emotion. The piano accompaniment is colorful and rangy (from atonality to “London Bridges”) and incorporates his own heavy breathing, tapping (even tickling the underside of the keyboard), whistling, humming, oom-pah-pahing, beeping, sighing, and groaning. And none of this sounds gimmicky. Wilde’s writing, he said, “is on the same level as Shakespeare”: “We are the zanies of sorrow.” “The final mystery is oneself.” “Love of some kind is the only possible explanation of the extraordinary amount of suffering that there is in the world.” Rzewski even throws in a timely passage from Wilde’s The Soul of Man Under Socialism: “All forms of government are failures.” The total impression was devastating.

As an encore, Rzewski pulled out a long-lost manuscript of his setting of Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” and once again accompanied his own eloquent reading (“The grave’s a fine and private place,/But none, I think, do there embrace”). I’d never heard him be charming before — he’s a master at that, too.

Rzewski’s early Les Moutons de Panurge (1968) turned up on the Bank of America Celebrity Series recital by the lower-case eighth blackbird, a new-music team of string and wind virtuosos who wear casual clothes, play largely from memory, and stalk freely about the stage while they’re playing. Their music-theater shticks included cellist Nicholas Photinos sawing a wooden board in half and two of the musicians collapsing on the stage along with the two halves of the board. This was the climax of Gordon Fitzell’s Lucid, one of three commissions from young composers for eighth blackbird’s 10th anniversary, “each taking its one-word title from a single line of the eighth stanza of Wallace Stevens’s poem ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird’: ‘And lucid, inescapable rhythms.’ ” (The other two pieces were Ashley Fure’s Inescapable and Marcus Karl Maroney’s Rhythms.)