Flip |

Thirteen years ago, a carpenter demolishing an old tenement in Amsterdam found 86 letters and postcards and one telegram hidden in the attic floor. They were all written in 1942 by a Jewish teenager, Philip “Flip” Slier, to his parents from a labor camp in Nazi-occupied Netherlands. The carpenter soon realized he had discovered a remarkable wartime document and delivered the missives to the Dutch National Institute of War Documentation, initiating a quest to put a face on this young man, a mere 18 years old at the time of the writings.

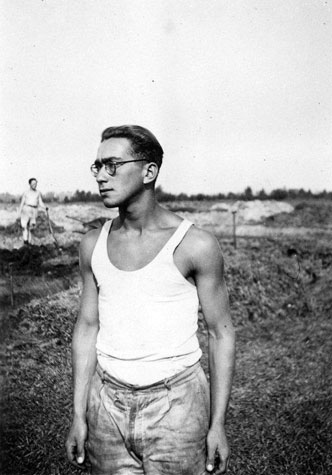

The result is Hidden Letters, a 200-page book that not only includes Flip’s correspondence, but also maps, documents, even Flip’s fingerprint on a soap coupon. And there are heartrending photographs, many of which were taken by Flip long before he knew his fate.

Recently published, the book is earning praise for its historical value and a poignancy that rivals Anne Frank’s diary. To commemorate Holocaust Remembrance Day, the book’s writers, Deborah Slier (Flip’s first cousin) and her husband, Dr. Ian Shine, will give readings at local colleges and temples, including Temple Emanu-El in Providence on April 11.

Slier, who is 78, never met Flip. She and her family (her father and Flip’s father were brothers) fled the Netherlands in 1922 and moved to South Africa, where she grew up. She later moved to New York and learned of the letters from a distant Dutch relative; she knew right away she had to tell Flip’s story.

Slier spent eight years researching the book, visiting the Netherlands five times, talking to Flip’s childhood friend, and reading other accounts of the war — all aimed at recreating what life was like for Flip during the German occupation. Writing the book was like “fitting together a puzzle,’’ says Slier. “I think that’s what kept the emotions at bay.’’ Still, often the details were so sad she’d have to stop: “He was just an ordinary boy.’’

Flip was about 5 feet 8 inches tall, weighed 156 pounds, and had wavy black hair and gray eyes set behind circle-frame glasses. He won and lost girlfriends, played the flute and mandolin, and loved to take pictures. An only child, he was adored by his parents.

He was working as a newspaper typesetter when the Germans invaded the Netherlands in 1940 and slowly prohibited Jews from working. Once unemployed, they were sent to nearby labor camps. Flip was dispatched to Moolengoot, where he dug ditches and wrote to his parents daily.

In his early letters, Flip had no inkling that his camp was a holding pen for death factories. He was chatty, almost cheery. “Have arrived in the camp,’’ he wrote April 25. “Reasonable bed, 3 blankets. Clean. Good atmosphere, decent people. A kiss from Flip.’’ He asked his parents to send him a windbreaker, a camp knife, clogs, a filter for his camera, a box of cookies.

As time went by, he sensed the danger, but still tried to be upbeat. “Please don’t worry about me being here,’’ he wrote May 24. “I don’t.’’ In one touching missive, he asked his parents to preserve his letters: “Pa, you can safely keep the letters. Put them in a corner somewhere, nobody will notice.’’

In June, he innocently wrote, “Pa, must we now hand in our bikes?’’ With food scarce, his empty stomach swelled. His tone soured and he despaired over fellow prisoners who were shipped off to Germany, where “the greatest terrors would be in store.’’ Still, he was hopeful the war would end. On July 8: “I keep my spirits up and hope that this will be over before winter arrives. That could really happen.’’

Of course, it didn’t. The war worsened and his letters, now censored, grew more desperate. His last letter was dated Sept. 14, 1942: “I am now terribly tired.’’ Horrified he might be sent to a concentration camp, Flip escaped and hid out in Amsterdam. He dyed his hair red, obtained false papers, and occasionally got to see his parents.

But on March 3, 1943, he was arrested at Amsterdam Central Station, waiting for a train to freedom in Switzerland. His offense: “Ohne Stern’’— without a star. One of the most disturbing documents in the book is his arrest record: “6 e) Shape of head,’’ is one of the questions, referring to the Nazi policy of measuring skulls to define Jews. The answer: “oval.’’

Flip was sent to S-Hut 67, the punishment hut at Westerbork transit camp. From there, he was herded onto a cattle truck to the death camp at Sobibor in Poland, where he perished, most likely in a gas chamber.

Hidden Letters ends with 37 signatures by Flip, all different, some purposeful, some playful, each from the hand of a young man experimenting with how to sign his name. That could be the scrawl of any teenager, anywhere in the world.