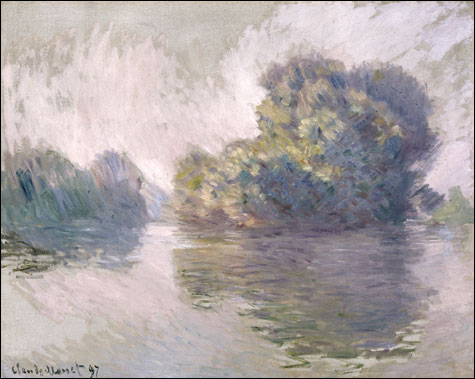

“THE ISLETS AT PORT-VILLEZ”: By Claude Monet, 1897, oil on canvas, 32 by 39 5/8 inches. |

| "Landscapes From The Age Of Impressionism" at Portland Museum of Art, 7 Congress Sq, Portland | through January 4, 2009 | 207.775.6148 |

Claude Monet’s “The Islets at Port-Villez” is the artistic and intellectual centerpiece of the excellent show “Landscapes from the Age of Impressionism” at the Portland Museum of Art. It’s the first painting you see coming into the gallery, and is the most purely “Impressionist” of all the pictures. It serves as the anchor for the show’s broader context.The show, which originated at the Brooklyn Museum, presents works by artists that influenced the Impressionists and artists who were, in turn, influenced by this most powerful of artistic movements. Thus we get to see Impressionists in the same gallery with works by the some of the Barbizon painters: Courbet, Daubigny, Breton, and others. We also see paintings by those who saw Impressionism and took some of what they saw into their own work, particularly the somewhat younger Americans, Childe Hassam, Sargent, and Twatchman. This is an opportunity to see and consider how artistic ideas radiated in those pre-reproduction days.

It’s important to remember that for its practitioners, Impressionism was mostly about technical issues, at least in the early days. They would get together and discuss, for instance, the best way to deal with the shadow side of a tree in the afternoon sun. It was only later, as their work developed, that it became clear that something other than simply a fresh style or new techniques was involved. Speaking toward the end of his life in the early 20th century, Camille Pissarro, a central figure of the movement, observed that they weren’t aware of the importance of what they were doing, while they were doing it.

Pissarro is represented in this show by a single, Cézanne-like work, “The Climb, Rue de la Côte-du-Jalet, Pontoise,” which doesn’t demonstrate his importance to Impressionism, and indeed to most advanced painting in France in the latter half of the 19th century.

He had come to France from the Virgin Islands to study with Corot, and was not only an early Impressionist, he was a central figure in the group. Manet might not be talking to Monet, and they both might be frowning on Cézanne, but they all knew and trusted Pissarro. He was not the greatest painter, and knew it, but believed deeply in the importance of what they were about and held the movement together, thus changing history. It’s beyond the scope of this exhibition, but later on Pissarro was an early champion of Seurat and van Gogh, and introduced Matisse to their work and to Monet’s, again changing history.

The Impressionists were looking for a way to represent the reality of the scene, shorn of preconceptions that artists and their public had about how things looked. They admired the Barbizon painters, especially Corot and Courbet, but found their work constrained and sometimes contrived. There was usually a narrative with their work, either implied, as in a lot of Courbet, or direct, as in Millet or, in this show, Breton’s “The End of the Working Day.”

Looking for something more, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and the others took their easels outdoors and tried to capture the real effects of color, light, and shadow. They were looking for a painting method that would render something closer to objective reality. What they got was a new understanding of what art was about.

For a clear view of the divide between Barbizon and Impressionism, compare Monet’s “Rising Tide at Pourville” with Courbet’s “Isolated Rock.” The Courbet is brooding and dark, presenting a melancholic, almost angry, narrative mood. The Monet takes an unusual point of view, looking slightly down at rows of parallel whitecaps, and the result looks odd and experimental, even more than a century later. The subject here is a record of the relationship between the scene and the artist, rather than an idea the artist wishes to express. We are looking at an attempt to allow us to see this moment through the eyes of the painter. This was a profound difference, a new understanding of the function of art.

This new understanding was needed. The world was indeed changing. Transportation, at least in Europe, was becoming fast and safe. Monarchies were on the verge of disappearing, as were hereditary aristocracies. The telegraph had spanned the world, so instantaneous communication was become routine. Photographs were becoming common and were taking over much of the documentary function that had been the staple work of artists.

This is a lot easier to see in retrospect than it was while they were living it. Monet, who is represented so well in this show, was the linchpin of the movement. His commitment to seriousness and his ability to follow his ideas with concentration and courage brought him to some outstanding results. His painting “Vernon in the Sun,” with its view across the water to a town with a cathedral, still looks radical. It glows as if the bright sunlight day it depicts were shining out into the gallery.