MYSTERY ACHIEVEMENT: "Somewhere in there is us," King says. |

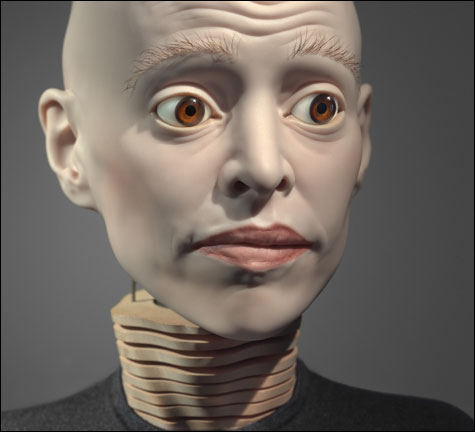

Visiting Elizabeth King's "The Sizes of Things In the Mind's Eye" at Brown University's Bell Gallery (64 College Street, Providence, through December 21) is a bit like visiting Dr. Frankenstein's lab — all glass eyes, artificial limbs, and automatons. And like a mad scientist, King concerns herself with the nature of life by focusing on the boundary between inanimate objects and living beings."Can I get you thinking about the inside of a small hollow thing in the shape of a head?" she has written of her lifelike, doll-like sculptures such as Myself with Other Eyes, a pale porcelain self-portrait head with blue glass eyes. The back of the head is missing and inside it is hollow. "This is my subject: The mystery of what goes on in there. Somewhere in there is us. We are inside looking out."

King, who lives in Richmond, Virginia, has made dolls resembling herself and her family members for three decades. This mid-career survey of some 65 sculptures, animations, drawings, photos, and installations was organized by the Visual Arts Center of Richmond, Virginia, and overseen here by Bell Galley director Jo-Ann Conklin.

The exhibit sets up a context for King's work by presenting in the Bell Gallery's sunny lobby cases filled with glass eyes, antique dolls, and plaster and wax life-casts of heads, lips, armpits, hands, and knees. There are also documentary videos about the history of clockwork dolls and a man making glass eyes.

This is a sort of behind-the-scenes preparation for the main gallery, which is dark except for King's videos and spotlit sculptures. Cases display a tiny eye, ear, and strands of hair that seem like studies on the way to building a full body. Pupil, a half-sized self-portrait, features a lifelike porcelain head with melancholy glass eyes atop a plain articulated wood torso, arms, and hands.

The scale and delicacy of King's figures suggests frailty. The heads are often bald and without eyebrows — recalling the hair loss associated with chemotherapy. They are uncannily realistic. Catching them out of corner of an eye, you might suspect they're moving. In Compass, a wooden hand actually does fidget ever so slightly. (Its movement is driven by a metal rod wandering over rotating magnets.) But King consistently breaks the illusion of life with doll bodies that recall wooden artists' mannequins.

A jerky stop-motion animation shows the Pupil sculpture seeming to inspect its body. In photos nearby, one of King's dolls tenderly places a finger to lips as if it has become self-aware. Its sad, thoughtful expression suggests a pain in this knowledge.

A case displays a tiny model eye standing before a video of such an eye blinking (via the magic of stop-motion animation). It makes you feel like you're being watched. Another case displays a little wooden hand mounted in front of a stop-motion animation of such a hand opening and closing, waving and pointing. The motion is so fluid, it seems as if the wooden hand has come alive. King has written: "Stop-action preserves the material realism and idiosyncrasy of the physical world, in all its stupendous and rich complexity, surprises intact. And these very qualities are the ones I want to foreground: a made object imitating a real one, first materially and then kinetically."

But King's craftsmanship, for all its vividness, feels fussy and uptight. And this constrains the ideas and emotions the sculptures can carry.

Which is disappointing, because King's ideas are expansive, pondering the source of the spark of life and the very nature of the soul. Her sculptures touch on a theme running through myth-ology from the golem to Pinocchio to Frankenstein to the Terminator, a theme made current because of our ability to manipulate the fabric of life via biotechnology. It is the story of the dangers inherent in manufacturing life, in playing God. Part of what haunts us about King's figures is their mix of naturalness and an abiding emptiness. What happens if we bring to life something that has no soul, something with no heart?

Read Greg Cook's blog at gregcookland.com/journal.