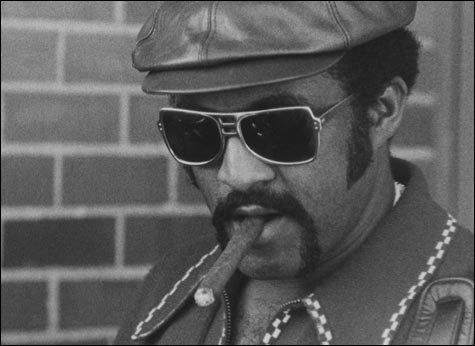

HAVANA BALL: Luis Tiant, seen here in his prime, was one of the all-time greatest Red Sox players. But his success came with tremendous personal sacrifice. |

There's something about Luis

Producer Bobby Farrelly talks about the star of his first documentary: “I’ll tell you this: he’s one of the most photogenic guys we’ve ever worked with. When the camera’s on him, it’s just a wonderful thing. He can just be there smoking a cigar and there’s something there that’s riveting. He’s stoic, and yet at the same time you get the feeling that there’s a lot going on in there — you can spend a little time guessing what he’s thinking. This [film] was certainly a departure from what my brother and I usually do. But we got the right guy. I just feel like we were lucky that he let us tell his story.” Review: The Lost Son of Havana. By Tom Meek. |

It had been nearly half a century since Luis Tiant stood on the Cuban soil where he was born, and where he first learned the skills that would see him become one of the greatest and most beloved pitchers in Red Sox history. But two years ago, even though he'd originally been denied a visitor's permit from both the Cuban and the US governments, he returned to the island for the first time in 46 years, as the coach of a goodwill baseball team.There, he had joyous reunions with relatives he hadn't seen in many decades. But he also saw the rusting '56 Chevy Bel Airs and the crumbling colonial architecture. And he saw how those relatives struggle to survive on a few dollars a month.

"It was good and not good," Tiant tells the Phoenix in his thickly accented English. "You happy you come back, but you no happy with what you see. The deterioration of everything. The buildings, houses, streets. It was hard watching the way people lived. When I left, it wasn't that way. It's tough. You go down and you don't know what to do. Cry? Or be happy because you go back to your country to see your family? It really disturb your mind."

His trip was documented by director Jonathan Hock, whose poignant, beautifully shot film The Lost Son of Havana (which was produced by the Farrelly Brothers and Kris Meyer), premieres this Saturday at the Somerville Theatre as part of Independent Film Festival Boston.

Tiant knew this would be an intensely emotional journey, and that many of the memories it dredged up would be wrenching. But he went nonetheless.

"I wanted to go and see," says the 68 year old. Otherwise, "I maybe die here before I get to go back."

Now, with Barack Obama in the White House and the headlines trumpeting a tentative thawing of US-Cuba relations — beginning with the announcement last week that the US will lift restrictions for Cuban-Americans wishing to travel and transfer money to the island — Tiant looks back on a life in which he's been exiled from his birthplace for five decades. In which he sent money home, only to have it confiscated. In which he was separated from his parents for 14 years. And he has one question: what took so long?

Cuckoo libre

"I'm not a political person," says Tiant, sitting in a booth at Game On! near Fenway Park, looking sharp in a black leather jacket with a Bluetooth headset clipped to his ear and a giant 2004 World Series ring on his finger. His famous Fu Manchu is now cottony white. It's the second most expressive part of his face, after his empathic, amber-colored eyes.

Certainly, one can't picture the jovial, cigar-chomping Tiant speaking as provocatively as the Sox' Mike Lowell did back in 2006, when news reports revealed that Fidel Castro was gravely ill. "I hope he does die," said Lowell, whose parents fled the dictatorship for Puerto Rico in 1960. "Castro killed members of my family."

But if Tiant isn't especially "political," his life has been indelibly touched by politics.

By the time of the 1959 Cuban revolution, Tiant had begun to establish himself as a power-pitching phenom on the baseball-crazy island. Castro — himself a pitcher manqué— took note.

"I met him twice," says Tiant. "He used to come into the clubhouse. The last year we play in Cuba, in '61, he used to come and shake your hand."

That year, Tiant was splitting his time between playing in Cuba and the Mexican League. But in the wake of the Bay of Pigs, Castro consolidated power and locked down the island. Having abolished professional sports, he gave an ultimatum to any Cuban athlete playing abroad: return and play as an amateur or don't come home again.