THE TRANSIENT EYE: Gardner allows us to consider that the worlds he has filmed so beautifully were disappearing as his camera rolled. |

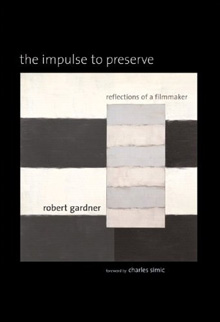

The flyleaf of The Impulse To Preserve describes Robert Gardner — for years the director of Harvard’s Carpenter Center of the Visual Arts and the creator of its film program — as a “nonfiction filmmaker.” This bland label is preferable to the dry and restrictive “anthropological” or “documentary,” but descriptions are inadequate. In all of Gardner’s films — from Dead Birds (1961), which is set among the Dani people of Papua, New Guinea, to Passenger, his account of artist Sean Scully’s painting a picture — there is a lyricism and a personality that lifts his work out of category. He writes, “the true nature of film resides in its capacity for storytelling.” Gardner’s work may be fact-based, but this has not crimped his imagination or his ability to tell stories.His book consists of diaries, letters, and photographs (more than 400) that chart his adventures in making films for more than 40 years in Indonesia, Africa, and Asia. The record will interest anyone who’s seen Deep Hearts, Forest of Bliss, or City of Lights. It’s also a practical education for non-fiction filmmakers similar to what John Boorman’s The Emerald Forest Diary and Eleanor Coppola’s Notes provide for those who make “movies.” But what gives Gardner’s book its kick, its emotional and intellectual impact, are his meditations, short essays in boldface type, at the opening and closing of The Impulse To Preserve.

The book opens with a photograph of a wrinkled, crawling African Pygmy woman. “In filming,” Gardner writes, “there is always a problem of conveying a true indication of scale; on the screen the head of a fly can look like a monster, and a toy boat on a tiny pool like a ship at sea. This may be why there are so many pictures of anthropologists with their hands on pygmies’ heads.” In other words, we need to remember that in the medium we commonly consider the most realistic, the problem is illusion. The filmmaker achieves a truth in pointing his camera and editing the results of what he sees, but he never achieves the truth.

Gardner says this in another and poignant way in the longer essay “Going Back,” where he returns to the Dani, with whom he spent an “enthralled” six months in 1961. Now it’s 1989, and he discovers, without surprise, that the world he knew and filmed is utterly changed. He’s sad, of course, but between the lines he strikes a deeper note. The world filmed is already past by the time we see the completed film — indeed, when the filmmaker sees the rushes, he’s looking at what will not happen again. Film’s greatest illusion may be its manipulation of time. We can read a book or a poem or look at a work of art forever. Time in live performance — theater, dance, comedy, music, the Oscars — is variable. But we’re in our seats for the time a film takes.

Gardner says this in another and poignant way in the longer essay “Going Back,” where he returns to the Dani, with whom he spent an “enthralled” six months in 1961. Now it’s 1989, and he discovers, without surprise, that the world he knew and filmed is utterly changed. He’s sad, of course, but between the lines he strikes a deeper note. The world filmed is already past by the time we see the completed film — indeed, when the filmmaker sees the rushes, he’s looking at what will not happen again. Film’s greatest illusion may be its manipulation of time. We can read a book or a poem or look at a work of art forever. Time in live performance — theater, dance, comedy, music, the Oscars — is variable. But we’re in our seats for the time a film takes.

Gardner allows us to consider that the worlds he has filmed so beautifully were disappearing as his camera rolled. Sentiment and nostalgia are built into film in a way that enhances its ability to touch our intellects and our emotions. And to do so, Gardner has, as the poet Charles Simic says in his introduction, refused to accept “the discord between reality and imagination.” He has been in the real world fully imagining, and this book is part of what he brought back.

“ART AND ARTIFACTS FROM THE TRAVELS OF ROBERT GARDNER, 1951–2001” | June 14-july 8 | Hurst Gallery, 53 Mount Auburn St, Cambridge | opening reception and book signing June 14, 5:30-8:30 pm | 617.491.6888

On the Web

Hurst Gallery: //www.hurstgallery.com