RADIO GOLF: Potent — and unusually straightforward for Wilson.

|

When Radio Golf, the last link of August Wilson’s great track through the 20th century, was laid in spring of 2005 at Yale, the ghost that hovered over it was that of Aunt Ester, the 300-plus-year-old Pittsburgh Hill District seer whose birth date corresponds with the arrival of African slaves on American shores. As the Huntington Theatre Company mounts the play 16 months later, the ghost in the rafters is that of Wilson, who died last October at 60, soon after completing this final piece of his grand project chronicling decade by decade the African-American experience of the last 100 years. It’s a monumental achievement, Wilson’s 25 years of plumbing what he considered the inexhaustible well of black life. The 1997-set Radio Golf (at the Boston University Theatre through October 15) is not Wilson’s crowning achievement; that would be Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, a top god in the pantheon of American playwriting. But if this story of lucre-lined “redevelopment” at war with down-at-heels but sacrosanct tradition lacks the musicality and rich spiritual patina of Wilson’s finest work, it is nonetheless potent — and unusually straightforward for the playwright, whose style could be digressive. And having seen the play at Yale, I can report that Wilson, a writer for whom creation was an ongoing conversation with himself, his characters, his collaborators, did not let liver cancer get in the way of his making it better.

In Radio Golf, Wilson takes on the upwardly mobile black middle class. Real-estate executive and mayoral candidate Harmond Wilks and bank vice-president Roosevelt Hicks are partners in Bedford Hills Redevelopment, which is on the verge of erecting a major project in the Hill District, complete with Barnes & Noble and Starbucks. Just two bricks need to fall into place: the Hill District must be declared “blighted,” so that the project qualifies for federal funds, and the “raggedy-ass” house at 1839 Wylie Avenue must be razed. One of the highlights of the production is the cocky, ecstatic Fats-Waller-meets-frat-man dance the former Cornell roommates do when word comes that the neighborhood of their youth has been officially declared blighted. But as aficionados of Wilson need not be told, the destruction of 1839 Wylie, where Aunt Ester guided Citizen Barlow to the “City of Bones” in Gem of the Ocean, is another matter. And when an elderly man turns up and starts painting the edifice, which he claims to own despite Harmond’s assurance that he bought the place from the city for unpaid taxes, the battle in on: between legal skullduggery and moral right, between tearing down one’s cultural legacy and building on it.

In David Gallo’s towering design for the Huntington, the clean, plasticky office of Bedford Hills Redevelopment is surrounded — and dwarfed — by the wreckage of the Hill neighborhood itself: a grand wooden structure rotting, its windows broken and its curtains torn. Other Hill characters also intrude on the space occupied by Wilks, his campaign-manager wife, Mame, the golf-obsessed Hicks, and all of their big plans. Looking for work is independent contractor Sterling Johnson, the ex-con of 1960s-set Two Trains Running, who 30 years earlier robbed a bank because he “just wanted to know what it was like to have some money.” Looking for “some Christian people” is Elder Joseph Barlow, the man who says he owns the house at 1839 Wylie. (Turns out both he and Harmond have connections to Gem of the Ocean.) Old Joe, thoroughly inhabited by the raspy Anthony Chisholm, is a wonderful character — a vagabond repository of Hill history, right down to the dates, with a simple if wily sense of justice. Sterling, too, knows right from wrong, and as far as he’s concerned, the war between Bedford Hills and Old Joe is the cowboys disenfranchising the Indians all over again. In one of those inspired Wilson moments, funny yet profound, he dons war paint to make his point.

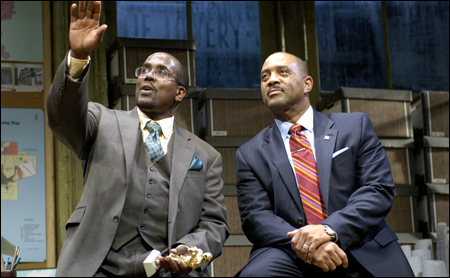

The nuanced Huntington production, directed by Kenny Leon, is well acted, as Wilson’s plays tend to be; sometimes I think they act themselves. Hassan El-Amin, as Harmond, gives a fierce performance that doesn’t entirely solve the problem of the character’s Saul-like conversion. Michole Briana White is foxy yet true-blue as Mame — at Yale an undernourished part that Wilson has fed dramatic protein, to which White adds a touch of minx. James A. Williams, as the assimilationist Hicks, wraps street toughness into the self-satisfied would-be mogul. Eugene Lee stepped into Sterling at the last minute for an ailing John Earl Jelks, but he wears the part as comfortably as he does the overalls.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

bobrauschenbergamerica: Mid-century America’s open spaces and inclusive spirit, its burgeoning dark corners.

|

In an American Theatre interview conducted by Suzan-Lori Parks, Wilson explained that he arranges his works like collages, gathering material and then shifting it around. In bobrauschenbergamerica (presented by American Repertory Theatre at the Loeb Drama Center through October 7), playwright Charles L. Mee turns Robert Rauschenberg into August Wilson: a collage artist whose canvas is the stage. Collaborating with director Anne Bogart and her rigorous SITI Company, Mee takes some of the bits and pieces that inspired Rauschenberg — from stuffed chickens and claw-foot bathtubs to outright debris — and strings them, along with other borrowings and caprices, into a whimsical, elegiac theater piece that is less about the artist than about the mid-century America that spawned him: its open spaces and inclusive spirit, its burgeoning dark corners.