Eight years after Loïs Mailou Jones’s death, School of the Museum of Fine Arts curator Joanna Soltan is proclaiming her to be “among the most significant African-American artists of the 20th century,” and her work resides in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. “Lois Mailou Jones: The Early Works,” on view at the Museum School through October 14, shows where she came from.

|

FOLK ART? Rojas’s exhibit suggests a dream from a land of fairy tales, Russian nesting dolls, and schoolgirl notebook doodles.

|

Jones was born here in Boston in 1905. Her mother ran a beauty shop and made hats. Her father, a building superintendent, attended night school to earn a law degree when he was 40. The family summered at Martha’s Vineyard on land her grandmother bought with money she earned as a housekeeper and nanny.

The exhibit centers on some 30 patterns Jones painted as a freelance textile designer in the decade after she received a degree from the Museum School and a certificate from the Boston Normal School (now Massachusetts College of Art) in 1927. In one, green and rose leaves jitterbug around bundles of red and orange flowers. Elsewhere, Art Deco patterns of geometric shapes and sharp zigzags shimmy to a big-band beat.

Borrowed primarily from the Loïs Mailou Jones-Pierre Noel Trust, with many being publicly shown for the first time, the works are well assembled to show how Jones developed her assured touch. She sought inspiration in Japanese prints, Chinese embroidery, and mediæval European tapestries. But the majority of her works here are conventional floral designs for wallpaper, curtains, and upholstery given a bit of spark by high key colors. One suspects she was hemmed in by trying to satisfy her employers — primarily the firms Schumacher in New York and F.A. Foster in Boston — and their customers.

While driving to Martha’s Vineyard one summer, Jones was thrilled to spot her designs displayed in the windows of interior-decoration shops. But the fabrics bore only the name of the patterns, not her name. “That bothered me because I was doing all this work but not getting any recognition,” she told a biographer. “And I realized I would have to think seriously about changing my profession if I were to be known by name.”

She began teaching art at Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina in 1928, then in 1930 moved to Howard University in Washington, where she would teach until 1977. But she got a year’s leave to sail to Paris in September 1937 and study art in what was then the cultural capital of the Western world. There she began painting in the dense post-Impressionist mode, somewhere between Pissarro and early Matisse, that she employed in her 1943 painting My Mother’s Hats, a still life of ladies’ hats arrayed on a table with a vase of orange flowers. There she found a culture that seemed less hung up on the color of her skin.

Jones continued teaching and painting upon her return, finding inspiration in Haitian art after she married a Haitian and began making regular trips to the island in 1953, and from African styles after she traveled to 11 African countries on a research grant in 1970.

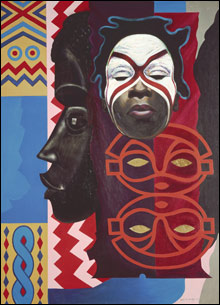

UBI GIRL FROM TAI REGION: Jones plumbed black identity in combinations of Western representational portraiture and abstract African designs.

|

Ubi Girl from Tai Region (1972) is the fruit of the latter voyage. In the bright, bold canvas, Jones contrasts traditional realist Western portraiture with the abstracted designs of traditional African art by combining a representational portrait of an Ivory Coast woman with a mask painted across her face; a traditional African weaving tool decorated with an abstracted carved face; masks from Zaire; and the flat geometric patterns of African textiles.

The painting seems at once a treatise on the influence of traditional African art on the Cubist paintings that sparked so much Western art in the 20th century and a summation of the lifelong inspiration Jones drew from the art of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Painting during an era when many African-Americans adopted African fashions and names to connect with their African roots, the mature Jones examines the construction of black identity by returning to textile patterns, the labor of her youth.

Clare Rojas’s exhibit “Hope Springs Eternal” at Brandeis’s Rose Art Museum suggests an odd, unfathomable dream from a nostalgic land of fairy tales, Russian nesting dolls, and schoolgirl notebook doodles. The San Francisco artist packs two floors with paintings of serious women in bulky floral dresses, silly naked men with dagger penises, and hooved beasts wandering about bright landscapes patterned after traditional quilts or the kaleidoscopic flowers and stars known as hex signs that began decorating Pennsylvania barns in the mid 19th century.