Two photographers currently showing their work couldn't be more dissimilar in their subject matter, yet they share the skill of perceptive social observation. “Fantastic Tales: Photography of Nan Goldin” is at the RISD Museum (through January 14), and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew’s “The Virtual Immigrant” is at the University of Rhode Island Fine Arts Center in Kingston (through December 10).

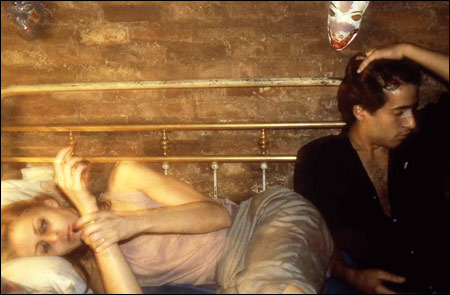

EMOTIONAL AFTERMATHS: Goldin’s “Greer and Robert on the bed, NYC” (1982).

|

Nan Goldin was hardly a voyeur in the 1970s when she began photographing drug addicts and drag queens, people having sex and people in the emotional aftermath. That was all part of her East Village world, so “Fantastic Tales” doesn't come across like a Diane Arbus outsider fascinated with grotesques but more like a Eugene Richards living with a family until they don't hide being sick or shooting up.

Drawn from a single private collection, the RISD show is nevertheless a comprehensive cross-section of 30 years’ work. In addition to 26 large photographs, there is a 27-print grid of images from the series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, arranged by the photographer in considered juxtapositions. A half-dressed very pregnant women leans against a bureau amidst a variety of informal portraits of women, most of whose expressions are thoughtful if not despondent. The last nine in the strip of images are of couples, most apparently happy but two signature Nan Goldin compositions: sprawled on a bed together but as removed from each other as if in separate rooms.

Particularly interesting in this collection are a sampling of images that show off Goldin’s eye for visual balance and evocative mood. There is a man stooping in a smoky volcanic landscape, his sooty backlit face as indistinct as an abstract mask. There is The sky on the twilight of Philippine's suicide, Winterthus, Switzerland, in which a lit street lamp and a smokestack stand stark against a cloud-roiled, blood-red sky. There are also two black-and-white photographs, one a picture of a drag queen wearing multiple pearl necklaces and, deadpan, offering a light to a handsome man smoking a cigarette in a poster.

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, an associate professor of art at URI, focuses on a subject personally important to her in “The Virtual Immigrant.” The title refers to the dual-culture international telephone call workers in Bangalore, where she was raised. In portraits and sound montages, she portrays and documents the psychological and social double vision of a subculture growing more common in India in this period of business process outsourcing.

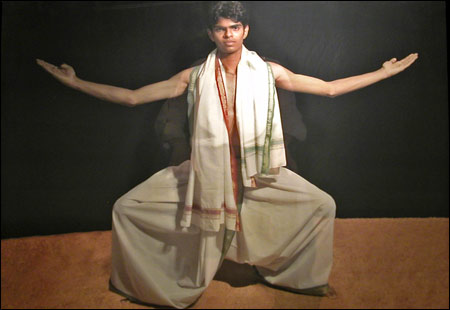

These are lenticular photographs, which you are more likely to find as a Cracker Jacks prize than on an art gallery wall. In them two images are reassembled behind the vertical lines of a lenticular “lens,” one showing the subjects in formal Indian dress and the other in casual, Western street clothes, ready for work.

In the catalog for the show, Matthew compares the results to a Venn diagram, in which overlapping circles show areas of commonality. In “The Virtual Immigrant,” this is more than a gimmick. Most of the color photographs show the subjects life-size or larger, so the morphing is particularly surreal as we pass before them.

|

The variety of the portraits accomplishes an additional effect, placing us amid a cross-section of personalities. Some appear exotic: as we enter the gallery, we are greeted by Anirudh, a seated young man in a gray long-sleeved shirt, whose head remains in the same position and with the same neutral expression as he changes into what could be a squatting figure dancing with bare arms outstretched. Some apparent personality changes are striking. Kirti shows both a slightly hunched denim jacketed young woman and a more confident one who beams at us in an orange sari. Dattatri has a motorcycle helmet under one arm in one of the images; his traditional garb in the merging photograph makes his expression appear more placid.

Telephones dangle in a corner, where we may listen to call center workers conversing about personal identity. They live in a social climate where television has taught them idiomatic American English but where family and cultural expectations may be decidedly non-American. A montage of these recordings provides a background soundscape as we walk about. The virtual immigrant immersion turns us into greater strangers as we view an array of 21 small black-and-white photographs titled “Memories of India,” many of which were in Matthew's excellent contribution to a group show at the Newport Art Museum earlier this year.