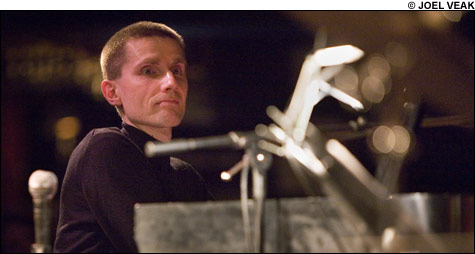

COMPLEAT: John Stetch has fingers, touch, time, and a healthy impatience with song form.

|

“I’ve got $30 — which three CDs do you recommend?” The fan was at the corner of the stage at Johnny D’s talking to guitarist Dave Fiuczynski, who was on his knees hawking about half a dozen of his discs with different bands at 10 bucks a pop. “This one is similar musically,” he said, pointing out the self-released Kif, for which the night’s band was named. “This one’s got the same kind of energy” — here he pointed to a disc by his band the Screaming Headless Torsos — “and this one’s punk jazz” — this by his band PunkJazz. One fan complained that he’d had to forgo his homework to get to this gig. “I haven’t done mine either,” Fiuczynski answered. “I’m gonna tell my teacher the same thing tomorrow: sorry, I didn’t get to that.”

Fiuczynski’s situation is typical for a Boston musician: involved in as many as half a dozen bands, on call when out-of-town friends like Don Byron need a pick-up band, teaching at Berklee, taking advanced courses at New England Conservatory. His band at Johnny D’s January 31 was a quintet configuration of Kif: saxophonist Nikolay Moiseenko, keyboardist Jim Funnell, bassist Jeremy McDonald, and drummer Louis Cato. Berklee-related all.

Kif’s theme at Johnny D’s was Mahavishnu. They opened with a medley of “Birds of Fire,” “Dawn,” and “Miles Beyond,” Fiuczynski sporting his Mahavishnu-like double-neck guitar, spitting out angular fusioned-up bop lines in unison with Moiseenko and Funnell, ornamenting them with John McLaughlin’s signature, sitar-like bends. And Cato was a wonder throughout the set — working against the low, broken-line syncopated throb of McDonald’s electric bass, he set up all manner of drum ’n’ bass speed riffs and hip-hoppy funk. Moiseenko played tart abstract runs out of Greg Osby/Steve Coleman and, when called for, David Sandborn/Jr. Walker blues licks. Funnell in particular built his solos — a variety of Fender Rhodes sounds and “straight” piano, in funky staccato blasts and spare, modal scales — against Cato’s beat. It’s a brainy, ferocious little band.

John Tchicai — the great Afro-Dutch reed player who made his name in the ’60s New York avant-garde and particularly on John Coltrane’s Ascension — has been visiting town more and more often over the past few years. His recording with saxophonist Charlie Kohlhase and guitarist Garrison Fewell, Good Night Songs (Boxholder), was one of the best of 2006, and Thursday night the trio convened at Rutman’s Violins (by Symphony Hall) for a short, sublime concert. The program, organized into a series of two-tune medleys, was less freewheeling than the CD, as if the trio were working up new pieces for the series of performances that would culminate later that week in a quintet gig with bassist Cecil McBee and drummer Billy Hart at Birdland in New York.

WHO’S GOT THA FUNK?: Chris Potter’s quartet didn’t need a bass player.

|

Tchicai’s original opener, “To Wibke and Peedoh,” took off from a beboppish unison ensemble line into overlapping lines by Tchicai’s tenor and Kohlhase’s alto while Fewell played a walking bass line. Fewell’s “Tribal Ghost” was a free-tempo lullaby duet between the guitarist and Kohlhase’s baritone. On Kohlhase’s “Doom Is Mine,” another beboppish line with stop-time rests, guitar danced behind two tenors, Kohlhase holding a low foghorn note while Tchicai took off into increasingly forceful rhythmic phrases, and then Kohlhase playing a quizzical a cappella response. One piece was laid over an abstract calypso figure from Fewell; another began with Tchicai reciting an A.R. Ammons poem. The last tune was based on a bluesy descending figure that turned out to be based on Monk’s “Friday the 13th.” It was a quiet, unassuming concert, animated by the band’s intimate musical conversation, and it was over in about 50 minutes when Tchicai — tall and dignified in a button-down shirt — announced, “That’s the end of the concert. Thank you for coming.”

At the Regattabar on Tuesday and Wednesday the 6th and 7th, meanwhile, saxophonist Chris Potter combined outer-edge explorations with funky accessibility. A veteran of the Dave Douglas and Dave Holland bands, Potter was touring with his Underground quartet, which he named for his 2006 Sunnyside release. Now, a year out, the album sounds too tidy by comparison with the early-Wednesday set I saw. Working without a bass player, Potter, Fender Rhodes pianist Craig Taborn, guitarist Adam Rogers, and the indispensable drummer Nate Smith built their pieces from subtly shifting grooves.

The masterful Potter has speed and articulation in all registers and a vivid imagination in his solos — muscular arpeggiated runs punctuated by honking shouts, melodic detours, muscular blues licks. But the details of his playing were secondary to the head of steam this band built on every tune. Smith would lay down a funky pattern on kick and top drums, with only a splash of cymbal here and there, while Taborn and Rogers worked spare, syncopated riffs. For such a funk-oriented group, there were open, misterioso spaces everywhere, Rogers punctuating a groove with, say, just one odd, perfect chord played on the first beat of each measure, Taborn tugging in the other direction with his bass-clef patterns, Potter building pieces from the motivic cells of his tunes.