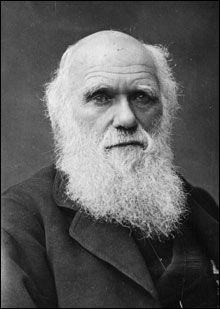

EASY RIDER: Darwin amused himself by riding Galápagos tortoises — as well as by pointing out how shell structure affects feeding behavior. |

On December 27, 1831, Charles Darwin sailed from Plymouth, England, an unpaid naturalist aboard the British brig HMS Beagle. It was a government-sponsored expedition to survey the coast of South America to develop maps that would help Britain protect its colonial interests. “Here I first saw a tropical forest in all its sublime grandeur,” Darwin raved from Brazil the following February. “I never experienced such intense delight.”In the Boston Museum of Science’s new “Darwin,” the great naturalist’s familiar tale unfolds like a drawing-room detective thriller, complete with Darwin’s magnifying glass. What he observed on his five-year circumnavigation of the Earth led to his theory of evolution, one of the seismic revolutions in how we understand the world. It’s an idea that’s proved enduringly controversial (this means you, Kansas and Pennsylvania), because Darwin doesn’t include God in his version of events. Some find this godlessness so repulsive that a tale has sprung up purporting that Darwin had a deathbed religious conversion and renounced evolution. The “tragedy of Charles Darwin,” according to the creationist Internets, is that he never did.

By the time of Darwin’s voyage, the idea of evolution was in the air, but scientists were mired in questions like whether giraffes’ necks grew longer to feed on high leaves. And if so, how could such adaptations be passed on? Further stymieing thinking was the generally held interpretation of the Bible that the world was only 6000 years old — not nearly long enough for evolution to take place. Fortunately for Darwin, geologists studying the development of rock formations were beginning to conclude that the world’s age had been underestimated by about 4.49 billion years.

When Darwin set off aboard the Beagle, armed with a tiny pistol, a Bible, and a club (on display here), he was a clean-shaven 22-year-old, eager for adventure. In the Brazilian jungle, he saw green iguanas. (The exhibit includes a cold-eyed live specimen.) He discovered fossils of an “extinct” giant ground sloth in Argentina and wondered why, over and over again, some species went extinct while similar ones survived. He shipped home thousands of specimens like the dazzling orange and green live horned frogs displayed here. Hundreds of these had never before been seen in Europe. It made his reputation as a naturalist.

The Beagle arrived at the Galápagos islands in September 1835. “Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance,” Darwin wrote. “A broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is everywhere covered by stunted, sunburnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life.” Exhibits display some of the critters (stuffed) that he soon spotted: flaming orange crabs, equatorial penguins, flightless cormorants, giant prickly pear cactus, blue-footed boobies, and iguanas that — unlike iguanas anywhere else — swam and fed in the ocean. Darwin, who in college had formed a club dedicated to eating animals “unknown to human palate,” reported, “These lizards, when cooked, yield a white meat, which is liked by those whose stomachs soar above all prejudices.” Bon appétit.

“TREE OF LIFE”: At the Museum of Science, Darwin’s familiar tale unfolds like a drawing-room detective thriller, complete with magnifying glass. |

One of the coolest parts of the show is the pair of giant live Galápagos tortoises, in bumpy gray-brown shells, that shuffle about on stumpy dinosaur legs. Darwin amused himself by riding these beasts. Nearby is a display of dead Galápagos tortoises that shows how tortoises from one island had “saddlebacked” shells that made it easier for them to reach up and munch tall local cacti while those from another island ate plants close to the ground and so made do with a dome-shaped shell.After sailing on, Darwin noticed that Galápagos mockingbirds differed from island to island too. The differences between finches of the different Galápagos islands were even more apparent, with beaks ranging from short and stout to long and pointy. Back home in England in 1834, he set about figuring out why. Of the many Darwin relics here, among the most striking is a tiny notebook from the late 1830s in which he scribbled “I think” and then a diagram of what looks like a bare twig. It’s an early stab at an evolutionary tree. He’s homing in on the big new idea, and the air is electric.

In 1838, Darwin read an essay about population growth by Thomas Malthus and was struck by the political economist’s idea that limited food supplies restrain the size of human populations. Darwin realized this could apply to critters as well. In 1842, he outlined his idea: plants and animals with advantageous variations were likely to live longer, thus leaving more offspring, some of which would inherit the beneficial traits. Over generations, this process of “natural selection” — his first use of the term — could create new species.