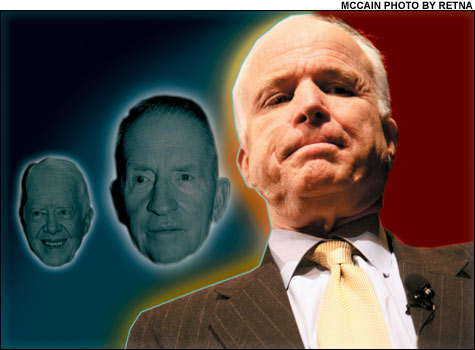

DARK SHADOWS: This time around, McCain seems unable to rouse the “radical middle” independents, as past mavericks have done. |

The biggest story of the campaign so far has been the semi-collapse of John McCain. Long expected to be the GOP front-runner and probable nominee, he has, instead, found his campaign foundering in second place, trailing Rudy Giuliani by double digits. Fundraising isn’t going as well as planned, and even reporters are finding that the charming “Straight Talk Express” of eight years ago lacks allure this time around. Now there’s even talk that his old friend and supporter Fred Thompson may enter the race and challenge him.

A lot of explanations have been offered for McCain’s stumbling start. For one, he is supporting an unpopular war (though, ironically, this should reinforce his reputation as a politician willing to call them as he sees them; plus, a fair number of Republicans still support the war). The party’s conservative base also doesn’t like him, for everything from his sponsorship of the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance reform legislation to his apparent friendship with John Kerry. It’s hard to run as an outsider when you’ve been the putative front-runner for so long. And at age 70, McCain can’t be the fresh face he once was.

McCain’s biggest problem, though, is that he is an anachronism. The movement he led in 2000 no longer has any followers. Even in the 2000 election, McCain wasn’t particularly popular with mainstream Republicans and trailed George Bush in the polls, much as he does now. However, he had lots of support from independents — and it was only when these independents were allowed to vote in a Republican primary (as in New Hampshire) that he did really well.

To understand why these independents no longer exist for McCain, just think of recent political history. The unusual force in American politics in the 1990s was the Perot movement. In 1992, H. Ross Perot attracted 18.8 percent of the vote — one of the largest outpourings of support for a third-party candidate in American history — and in 1996, he got 8.4 percent of the vote. Perot’s appeal was based on a number of things. But primarily, he offered voters a version of what Michael Barone has called “the man on horseback” — a somewhat militaristic, non-political figure who emerges out of nowhere and promises a new kind of leadership to save the country.

In fact, the antecedents of the Perot phenomenon came from the Jimmy Carter campaign in 1976. Both ran as outsiders, energizing a kind of “radical middle.” Both offered a kind of “engineering” approach to governing — offering non-ideological and practical approaches to politics. Both ran as businessmen, offering to bring the principles of commerce to governing. And, not coincidentally, both were graduates of the Naval Academy, where they developed their similar approaches, including a taste for autocratic chains of command, a distaste for politics as usual, and an unusual tolerance of personal freedom.

McCain is a product of this tradition, right down to the Naval Academy education. And, in retrospect, it’s clear that his base of support in 2000 was composed of the same kind of independent voters who had once admired Carter and made up the base of the Perot movement. (McCain even hails from the West, Perot’s strongest region.) McCain was, in fact, a more stable, less eccentric Perot.

The problem for McCain now is that the Perot movement no longer exists. It began to fall apart as the country became more partisan, beginning with the Clinton impeachment. The results in 2000 — when Ralph Nader’s candidacy cost Al Gore the presidency — only increased the sentiment that a vote for an independent-thinking candidate was a wasted ballot.

By polarizing the country, the Iraq War has also decreased demand for a third party, non-political figure, especially one who comes out of a military tradition. As a result, the same John McCain who was so popular in 2000 (though again, not so much with Republicans), isn’t nearly as admired today. In fact, in a country that now prizes party purity, “independent” politicians who bridge the gap between the two parties — Joe Lieberman comes to mind — are among the most disliked figures on the Washington scene.

Sadly for McCain, there isn’t much he can do to remedy the situation. He appears to be no more acceptable to conservatives in his party than he was in 2000. This time around, independents are as likely to vote in the Democratic race as they are in the Republican one. And, even if the third-party route were to open up again in 2008, figures such as New York mayor Michael Bloomberg would make far more credible independent candidates.

To be sure, McCain isn’t finished because Giuliani could stumble. But it is hard to see how the former soldier will get himself out of this quandary.