ALMOST: Pevear and Volokhonsky do get us closer to Tolstoy’s Russian than any other version has. |

| War and Peace | by Lev Tolstoy | Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky | Alfred A. Knopf | Xviii + 1273 pages | $37 |

War and Peace is the epic to end all epics. At 1400 pages, it’s too much for many readers. It was almost too much for Lev Tolstoy. He wrote it between 1863 and 1868, intending at first to draw on his experiences in the Crimean War — but to explain that event, he found he had to go back in Russian history, to the Decembrist Uprising of 1825 (when army officers protested Nikolai I’s assumption of the throne), and even that wasn’t far enough. War and Peace wound up treating the Napoleonic Wars, from the battle of Austerlitz in 1805 to the battle of Borodino in 1812, with an epilogue that spans another seven years.Tolstoy himself described the book as “not a novel” — and it most certainly isn’t. He meditates — or lectures — on war in particular (how Russia lost the battle of Borodino but subsequently defeated Napoleon by running away and refusing to fight) and war in general, on the individual talent (Napoleon versus Russian commander Mikhail Kutuzov), on the individual versus society, on free will versus determinism, on the meaning of history, the meaning of existence. A panoply of characters ghost through this panorama: the Rostov family, especially Nikolai, his sister Natasha, and their cousin Sonya; the Bolkonsky family, especially Prince Andrei and his sister Marya; Prince Vassily Kuragin and his children, Ippolit, Anatole, and Hélène; fat, good-natured Pierre Bezukhov. Some figures, like Anatole Kuragin and Boris Drubets-koy, glow brightly for a time and then fade away; some, like the officers Denisov and Dolokhov, thread in and out of the tapestry without resolution. Tolstoy’s habit of telling you everything about these characters (who they are, what they know, how they feel), rather than letting them reveal themselves, is irritating till you realize — perhaps from listening attentively to his lectures — that he actually doesn’t know, that no one can know what Nikolai is thinking or Natasha is feeling. War and Peace is a dialectic; you could argue that the most important word in the title is “and.” It even has two Tolstoy alter egos, Prince Andrei and Pierre.

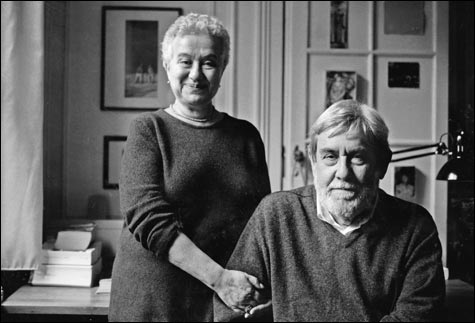

The husband-and-wife team of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky have already produced well-received translations of Dostoevsky’s novels and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. In his introduction to this volume, Pevear argues that “Tolstoy’s prose is an artistic medium; it is all of a piece; it is not good or bad Russian prose, it is Tolstoyan prose.” He goes on to cite R.H. Christian in Tolstoy: A Critical Introduction (1969): “Clumsiness and simplesse apart, no English version of War and Peace has succeeded in conveying the power, balance, rhythm and above all the repetitiveness of the original.” This War and Peace is more faithful to Tolstoy than any other, especially in not “correcting” his repetitiveness. The rhythms of Russian — Tolstoy’s or any other writer’s — are not those of English, however, and hewing more closely to the original can lead to awkwardness. The English-rather-than-Russian elegance of early translators like Constance Garnett and Louise and Aylmer Maude (the Maudes knew Tolstoy and had his approval) shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand.

A quick read-through also turned up more errors than one might have expected. In the list of “principal characters,” Anatole Kuragin is identified as Prince Vassily’s elder son; yet both the text and every translation (this one on pages 6 and 224) identify him as the younger son. (Ann Dunnigan, Anthony Briggs,and the Barnes & Noble edition of Garnett make the same odd character-list mistake.) In the very first line, “Gênes et Lucques” becomes “Gênes and Lucques,” the “et” having been translated when it shouldn’t have been; and on page 262, in the rendering of Weyrother’s German-language disposition for the attack on Napoleon’s troops at Austerlitz, we get “we far outflank his left wing with our right” when it should have been “we far outflank his right wing with our left.” (Pevear tells us that the translations of French and German that Tolstoy provides “are occasionally inaccurate, perhaps deliberately so,” but on this occasion Tolstoy was correct.) On page 167, “I was going to ask” becomes “I was going to asking” (there’s nothing odd about the Russian here); on page 816, “prosperity” comes out “propserity” (what happened to spellcheck?). On page 962 we get “Novodevichye Convent” instead of “Novodevichy,” neuter instead of masculine. One could ask why feminine names are masculinized: Princess Drubetskoy rather than Drubetskaya. (No one turns Anna Karenina into Anna Karenin.) A map of Austerlitz would have been nice. And consistency in the use of the indicative or the subjunctive in “as if” clauses.