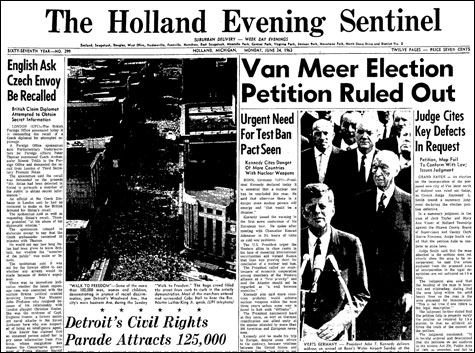

Click the image to read the Holland Evening Sentinel's account of Detroit's civil-rights demonstration from June 1963.

|

On Sunday, June 23, 1963, 125,000 people marched down Detroit's Woodward Avenue to the Civic Center, in what was described at the time as the largest civil-rights demonstration in the nation's history. According to the next day's account in the Holland Evening Sentinel

, the crowd at the Center "lustily booed," when representatives of Governor George W. Romney read a proclamation declaring "Freedom March Day in Michigan."

But Martin Luther King Jr. didn't fault Romney for his absence, which the governor ascribed to his policy against public appearances on the Sabbath. "At a news conference following the march . . . [King] refused to criticize Romney for not attending the demonstration," the Sentinel reported.

"Issuing the proclamation, and sending his personal representatives, was probably more than 49 other governors would have been willing to do at that time," says Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project at Stanford University. "It took considerable courage."

Romney would go much further, participating in a small demonstration in Grosse Pointe later that week; refusing to endorse Barry Goldwater in 1964, largely because of Goldwater's vote against the Civil Rights Act; and, in 1965, marching in Detroit to protest the police actions in Selma, Alabama.

These acts placed him at odds with his political party and with his church leadership. They are the types of actions, in defense of principles and at the risk of ambitions, that appear to be lacking in Romney's son — a failing that leads him, repeatedly, into false or exaggerated claims such as the one that has him in trouble this week.

Mitt Romney never questioned or decried the Mormon Church's doctrine forbidding black priests, which continued until 1978, at which time Romney was 31 years old, a vice president at Bain & Company, and the father of four.

So, for evidence of a principled stand he never took, Romney appropriated his father's principles. But, unlike King himself, Romney was not satisfied with what George Romney actually did. He inflated it, placing his father into the iconic position of marching alongside the civil rights leader.

He didn't just use imprecise language, as his campaign is now spinning it. His language — in at least three different nationally televised instances, including this past Sunday's Meet the Press with Tim Russert — was precise enough: he had direct, personal first-hand knowledge that his father had marched with Dr. King.

The precision, in fact, is the problem: the sincerity with which he offered the memory, the emotion that led his eyes to well up. This was not a man simply passing along something he had once come across in a David Broder book.

And yesterday, after being called on the issue, he offered more specifics. He told reporters in Iowa that he recalled his father changing his mind, and deciding to march even though it was Sunday.

It wasn't the first time Romney has abused a parental memory. Running for Senate in Massachusetts, in 1994, and trying to establish pro-choice credibility that he had done nothing to earn, Romney told stories about his mother, Lenore Romney, running on a strong pro-choice platform in her own unsuccessful bid for public office in 1970. Those tales were debunked by Boston Globe columnist Eileen McNamara.

Then, as now, Romney tried to buttress his statement with weak documentation at odds with the precision of the claim: in that case, Romney provided the Globe with a vaguely-worded campaign document that could be read as supporting the pre-Roe v Wade status quo, in which abortion was a felony in Michigan. ''I support and recognize the need for more liberal abortion rights while reaffirming the legal and medical measures needed to protect the unborn and pregnant woman [sic]," the document read.

Again, at that time, Romney did not just pass along falsehood as fact. He sold it as personal truth, speaking of the painful memories of a close relative's death, from complications of an illegal abortion.

Romney was telling that tale, of course, when it was politically expedient to be pro-choice. Today, needing to be pro-life, he has a new, highly personal and emotional tale of personal conversion after a doctor showed him how stem cells are handled in research — another specific but uncorroborated story, about which even the doctor involved has expressed skepticism.

Romney once favored gun control; now, needing gun-rights voters, he has falsely claimed to be a "lifelong hunter" and to have been endorsed in 2002 by the National Rifle Association – an endorsement the NRA never gave him. Needing to establish anti-illegal-immigrant credentials, he boasts of an attitude that he never displayed while governor — when he expressed no concern over several "sanctuary cities" in the state — until the very end of his term, when he had turned his attention to the Republican Presidential nomination.

This week, he finds the need to attack Mike Huckabee on crime, and so Romney has re-invented his record there, falsely claiming, in a new ad, to have cracked down on methamphetamine.

It is not just that these are untruths. They are the actions of a man desperate to cater to the whims of his audience. What they want, he must appear to be.

This is the opposite of leadership — the opposite of the actions taken by his father in the 1960s.

It should be recalled that the infamous "brainwashed" comment that sunk George Romney's 1968 Presidential candidate, cost him not merely because of the choice of words, but for the idea he was expressing: that what the generals were telling America about how the war was going in Vietnam was untrue.

That was heresy among pro-war Republicans, who quickly turned on Romney.

Today, Mitt Romney is attacking Huckabee for daring to criticize George W. Bush's conduct of the Iraq War, in a recent Foreign Affairs article. Romney, of course, has refused to speak ill of Bush — that would hurt him among the Republicans he is courting. His father, one suspects, would be disappointed.