“A promoter once said, ‘If there’s a recession, book the Kinks.’ ”

|

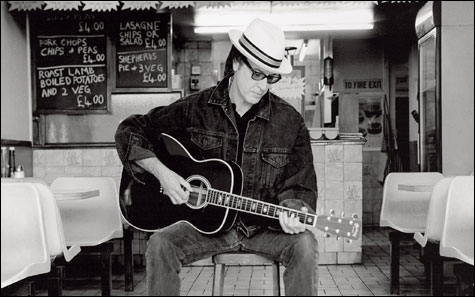

Ray Davies, 63, and his brother Dave, 61, fronted the Kinks from 1964 to 1993. They’ve been at odds with each other even longer. During the mid-to-late ’90s, Ray took his songbook on the road with another guitarist, playing stripped-down Kinks songs and telling stories. Two years ago, Ray — who’d been shot in the leg by a mugger in New Orleans in January 2004 — re-emerged with the Other People’s Lives CD and toured with a band. He’s just released Working Man’s Café (both CDs are on V2), which often considers a world in disarray and decline. Ray, with a backing quartet, is at the Orpheum Sunday, and they’ll likely play half a dozen songs from the new album. I talked with him by phone from San Francisco.

There’s a rumor that the original Kinks — you, drummer Mick Avory, and bassist Pete Quaife — might get together to record and/or play live, but Dave is the holdout.

That’s about it, as far as I know. My brother’s recovering really well. [Dave suffered a stroke in June 2004.] He’s done some recording. He just doesn’t want to spend a long time in the studio or on tour. I think we’re going to have to sit down and talk about it. I know the others really want to do it. I’d like to make something new as well as play the old songs. But Dave is the stumbling block, partially because of a genuine recovering issue and secondly, his state of mind and whether he feels he’s comfortable doing it.

And, of course, there’s your relationship.

Yes. But I think at some point in life you’ve got to try and bury some of these old things. There are things you can’t put your finger on, why people get annoyed with each other. It’s like anything else to do with family, and the Kinks are a family.

This band, how do you compare with the Kinks?

Obviously, it can’t recapture the Kinks records, but it [the music] is done with different emphasis. What is great is that new songs really have a life of their own. As players, they feel they’re bringing something new to it.

You’ve talked with me about the Kinks’ golden age of the mid-to-late ’60S and how you could never write anything like The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society again. But with Working Man’s Café you may be coming back to that area.

Village Green was done when we may not have been able to come to America. And on this one, my touring band wasn’t available. I wanted to start recording it very quickly and get it done. So I phoned up [producer] Ray Kennedy in Nashville, who wanted to do the first album, and he said, “Yeah, I can make this record in a week.” I wanted a straight recording, a singer-songwriter record, no real upstaging, not too many guitar solos, and that’s basically what Village Green is.

The viewpoint?

Remember Jacques Tati, a French cinema comedian? He used to walk through situations where the buildings would fall down just as he left. He’d walk on obliviously through the world, see disasters happening all around him. Think of it that way. There is dark humor, but it’s still humor.

Last year, there was an exhibit on the brain at Boston’s Museum of Science, and there was a list of famous manic-depressive, or bipolar, people. You were on it.

Why did they put me there? I’m not. Like everybody, I get depressed from time to time, but I get depressed when I can’t do my work. I’m a frustrative-obsessive.

You told me once that the Kinks were the only band where you could be over the moon with excitement and still walk away disappointed.

I don’t think I meant it in the sense that the audience will be disappointed; it’s more from the person’s point of view going through the exercise. I equate this to a marathon runner. You train four years, deny yourself the things you should be doing — like having a life — for one event. You win and then think, “Was it worth it?’ Sometimes, it was like that with the Kinks. We’d go through a lot of ups and downs, and I’d think sometimes we could have achieved less and been just as happy. Now I’ve got this record out. I’m really proud of it, but there are things I could have done in the past 18 months that may have been more worthwhile. But the work stands. It’s there.

On Working Man’s Café, once again, you deal with hard, changing times — with globalization, and the effect on common people. Maybe your time has come again.

A promoter once said, “If there’s a recession, book the Kinks.” He said it was because we resonate more in times of economic crisis. People start to think about the real issues in their life and are less materialistic.