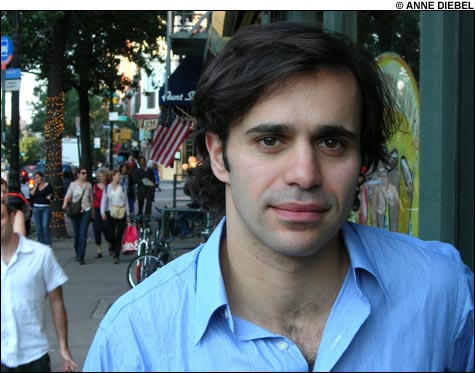

Keith Gessen reads at Harvard Book Store on April 23 and at Newtonville Books on April 24 |

Keith Gessen, 33, Harvard grad and former Newton resident, is the author of All the Sad Young Literary Men (Viking) as well as editor and co-founder of the Brooklyn-based literary mag n+1. The novel (which takes its name from the F. Scott Fitzerald story collection All the Sad Young Men) follows the undergrad and post-grad romantic, intellectual, and political adventures of three Harvard guys, Mark, Sam, and Keith. n+1, meanwhile, has been called “unabashedly highbrow,” an aggressive East Coast counterpart to the laid-back San Francisco lit mag the Believer, as eager to take on gossip blog Gawker as the Virginia Tech shootings. When I talk to Gessen via phone from Brooklyn, he speaks quickly, with a friendly, nervous laugh, in cadences that sound like a cross between Ira Glass and Martin Scorsese.

One of your characters becomes involved with “the Vice-President’s daughter” at Harvard. Did you know one of the Gore girls? Is that based on your experience?

Very loosely. I was in school in the same time as one of them, but most of that stuff is made up.

It struck me as problematic to use a real, living person in a fictional narrative.

The idea was to try to find a way to communicate how someone would be disappointed politically and also very personally by the election of 2000. None of this stuff happened to me with regard to his daughter at school, but I still felt extremely personally invested in a political campaign in a way that I’d never felt. And also, nothing that bad had ever happened. Certainly in my lifetime. I still think it’s the worst thing that’s happened in long time. And I feel like it’s something that for me — I was 25 and I was just becoming politically conscious — it still feels like it was more alienating with regard to America than anything that’s happened in my lifetime. It was more surprising than September 11. To me, we’d always expected that we were going to be attacked, but the idea of a right-wing coup [laughs] was less expected. That was something that was much more in the realm of fantasy than these attacks.

When Sam goes to Israel and spends time in the Palestinian West Bank village of Jenin, he argues with himself and finally concludes, “the Palestinians were idiots, but the Israelis . . . were fuckers.” Do you agree with him?

Yeah. I did go to Jenin in the summer of 2002. We had invaded Afghanistan and we were preparing very slowly to invade Iraq. Things didn’t quite happen the way I’ve described them, but that was a conclusion that I came to. But I wrote the novel pretty recently, and I was worried that things were going to change. But they really haven’t changed very much. They’ve deteriorated, but kind of in the same direction. So unfortunately that story still stands.

Reading the recent n+1 pamphlet What We Should Have Known, I was struck with how the panel you had assembled talked about these very highbrow books by Adorno and Foucault with a fannish, very down-to-earth enthusiasm, as if they were indie-rock nerds talking about their favorite albums.

Because we’re in America, I think, and because there’s all this important business that America conducts, there’s a feeling that the business of books is not an important business. And anyone who thinks otherwise is just Peter Pan. It continues to be weird to me that even within American literary culture there’s an embarrassment about books and how important books can be. There’s a kind of love of books. You know, people are like, “I love books.” But there’s always a kind of apology. The whole revival of the idea of genre fiction, where people are saying, “Well, we’re not really writing literature, we’re kind of doing a mass art.” That feels to me like a form of apology.

I recently heard John Banville talking about the noir mysteries he’s writing, and he took issue with commentators who called his noirs “literary.”

A few issues ago, n+1 had a symposium on American writing, and one of the pieces was by an editor at Doubleday who’s been there a long time, and he said, “I still remember the moment when I first heard the term ‘literary fiction.’ ” And it’s one of these things that’s been institutionalized, and it’s kind of changed the way people write. It’s created this new subset of things that are just literary. And so you have these books that are for the people, and then you have these literary books. And boy, I hope my book’s not literary!