BOTTOM LINE? Morris should have followed his chain of responsibility all the way to the top. |

For Errol Morris, film doesn’t show reality, it organizes it in an attempt at arriving at the truth. That makes for some apt but unlikely associations, as in Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, and some startling revelations, as in The Thin Blue Line. Applied to a loaded subject like the prisoner-abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib — a subject about which everyone seems to have an opinion based on the seemingly irrefutable evidence of the horrendous and now iconic photographs — such an approach faces tremendous challenges. As in: where to begin.

For Morris, a former private eye himself, it starts with the facts. Forget about the issues of the Iraq War and the use of torture in the War on Terror. What really happened at Abu Ghraib, before and after those pictures were taken and outside their frame? Who participated in the events? And who took the photographs?

And so he digs up the “bad apples” despised by both left and right, the handful of enlisted men and women investigated, charged, and convicted by the military in an attempt to clean house. Branded as scapegoats, poster children for an evil administration, traitors to the cause — what is their story?

This strategy will probably please no one, and understandably so. Myself, I’d rather see a film take down the people at the top who were responsible for the mess than one rehabilitating the losers who took the rap. True, I’m impressed by one of SOP’s more intriguing special effects, which puts together a virtual version (a form of it is available on www.errolmorris.com) of Army investigator Brad Pack’s synchronizing of the images culled from the three cameras involved in the scandal. This process expands beyond the single images and shows what really happened — often different from, and in some ways worse than, what’s widely assumed. It’s fascinating in its ontology, but what I really want is a virtual flow chart following the chain of command extending from creepy Charles Graner, the apparent ringleader of the squalid crimes, and reaching to the top. One that goes not just outside the frame but outside the prison, and perhaps into the Oval Office.

That’s another movie. Although not entirely. The interviewees bring up this context from time to time. Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, who was in charge of the unit responsible for much of this mischief, tells of pressure from top brass, pressure that one presumes emanated from then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Lynndie England, she of the notorious leash photo, points out that naked prisoners were being handcuffed with panties on their head before she got there: “The example was already set.” And sweet-faced Sabrina Harman, posed smiling with thumbs up next to the battered face of a dead Iraqi, was in fact providing the only surviving evidence of a CIA murder.

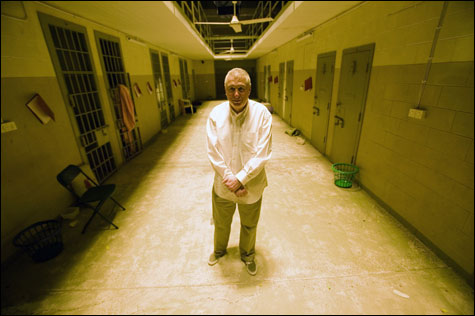

The bad guys who committed that murder got away. They’re the ghosts shown in a recurrent cutaway shot of a prison corridor prowled by faceless agents like a promotional blurb for Most Haunted. Maybe someday there will be a documentary about them. SOP has its own insights to offer, however, in its emphasis on the pawns sacrificed in the cover-up. Framed by Morris’s “interrotron,” they make excuses, they explain away the situation, but they take no responsibility. They feel sorry for themselves but spare little remorse for those they tormented. They learned too late the most important standard operating procedure of them all — cover your ass.