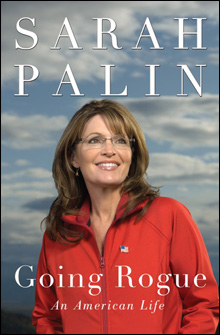

Sarah Palin,Going Rogue: An American Life

432 pages, HarperCollins, November 17, 2009

Highest Position Reached on NYT Best Seller List: No. 1 (4 weeks)

Readability: 7

Digestibility: 5

Crazy Factor: 0

Overall Score: 12

Few people have been given as good a story to tell as Sarah Palin. It's like a movie treatment: small-town, small-state gal, smart and successful in her world, gets plucked up and dropped into the middle of the rank lunacy that is a modern United States presidential campaign.

It is unfortunate that Palin, despite her obvious intelligence and wit, lacks the self-awareness and reflection to tell it well. Her memoir is readable, and often engaging, but relentlessly self-serving and disingenuous.

Palin is incapable of finding fault in herself or admitting to error. Her pat descriptions of events seem designed to shield any embarrassing or controversial revelations. The effect is to deprive the reader of any sense that Palin has suffered any real setbacks — which makes it impossible to empathize with her, or appreciate how her character has developed through those challenges.

She reveals no significant family problems growing up; she breezes through her obviously messy college years in a couple of uninformative pages; she admits to no marital tensions caused by the long separations from her husband, who lived and worked out on "the Slope" through much of their marriage; she tells a thoroughly unconvincing tale of how her oldest son came to enlist in the military; and as for Levi Johnston, the father of her grandchild — he is so absent from Going Rogue, one almost gets the impression that Tripp resulted from a virgin birth.

When she gets to her version of events on the presidential campaign trail, her whitewashing turns particularly mean-spirited. The body count of those Palin pushes under the bus runs too high to track.

Much has been made of this book being Palin's raised middle finger to the McCain staff, but to me that is only part of the book's larger message, which is a raised middle finger to professionals of all kinds.

Palin is convinced that expertise, education, experience — in other words, the things she lacks — are at best useless, if not actual impediments to success. All one needs is "common sense" — a magical phrase repeated so often in her book that, by the final chapter, like a pawn reaching the eighth rank, it is bequeathed capitalization and single-word status, as in "Commonsense Conservative."

At no time, it seems, can Palin imagine that anyone might know better than she, even though they might be the elite professionals in their fields. She even submits her own sketches to the Saturday Night Live writers, because their script "wasn't all that funny."

After her 10-week journey in Wonderland, Palin returns to Alaska an unchanged person. Along the way she learns no lessons; she is only reminded of the truths that lie in her favorite (usually misquoted) aphorisms about plain folks and hard work.

All of this is unsurprising in a political memoir — rarely much of a self-reflective exercise, especially for pols still early in their careers — but it's more disappointing from a legitimately fascinating person with a uniquely interesting experience to recount. Unfortunately, telling that story, honestly, would be going a little too rogue for Palin.

Instead, this self-proclaimed truth-teller seems to have used this book to adapt her life story to fit the mythos of the movement-conservative marketplace. For them, she is the plain-folk hockey mom, the corruption-fighting maverick, the perfect mom, the true conservative, the modern Esther (whose line, "If I die, I die," Palin uses twice in the book), and the martyr to the liberal-media attack machine. Any resemblance to the real Sarah Palin is purely coincidental.