Even though he’s headed to prison, SPEK will still be visible in Massachusetts. The Reading-spawned graffiti icon, whose real name is Adam Brandt, has hundreds — if not thousands — of modest scribbles and ornate masterpieces spattered across the Commonwealth. In Salem, which is ground zero for the massive North Shore graf scene — and where he was recently sentenced to four months for tagging and vandalism — his tag is sprayed on dumpsters, brick walls, street signs, and every other type of flat surface imaginable. Barbed-wire fences hardly proved obstacles. As a teeming graffiti force, SPEK rarely encountered train yards and abandoned buildings that he couldn’t infiltrate.For those reasons, he’s considered by both fellow taggers and law-enforcement officials as one of an elite bunch of exalted bombers — not all of whom are affiliated — who instigated an unusual police action this past December. A dozen town and city police departments joined forces to share information on the region’s heaviest graffiti hitters and hunt them down. While such police cooperation is de rigueur for more serious crimes, it is a brand-spanking-new strategy in the graffiti world. And whereas previously a captured artist/vandal usually faced community-service hours and fines, this new effort — spurred on by angry citizens in communities affected by the graffiti — is targeting an unprecedented number of taggers for jail time.

If SPEK was a Moby Dick of sorts for the consortium of Bay State vice squads, Boston Police Department (BPD) Detective William Kelley and MBTA Police Lieutenant Nancy O’Loughlin have been SPEK’s Ahabs, chasing the outlaw artist for a decade. But SPEK is far from the only big fish reeled in as authorities and community groups have cast a wide net from Marblehead to Dorchester. In October one of SPEK’s rivals, New York graffiti queen UTAH, was charged with 33 counts of tagging for her handiwork around Beantown. UTAH, born Danielle Bremner, is a member of the international crew Dirty 30, who from 2006 to 2007 heatedly competed for visibility with SPEK and his outfit, ITD (Illustrating Total Destruction). That same month, another veteran vandal, Tyson Andree Wells, who’s better known as CAYPE, was sentenced to one year in the South Bay House of Correction.

Exactly 12 months into this far-reaching regional law-enforcement campaign waged by the unofficially dubbed Greater Boston Area Graffiti Task Force, taggers are on the run, and at least five Krylon kings have been nabbed in the largest Bay State graffiti crackdown of this millennium.

After a nearly two-decade cat-and-mouse struggle, it appears that anti-graf cats have finally discovered how to reduce the amount of illegal street art in Eastern Massachusetts. While taggers have for years maintained the upper hand by relocating to neighboring locales when their own hoods got hot, authorities are now wising up. Highly visible taggers like SPEK and CAYPE have become trophy kills for the authorities, and their captures are being trumpeted as a warning to others. It’s a reality that both law-enforcement touts and taggers are willing to concede: for the first time since North Shore communities were overrun with graffiti in the early ’90s, the most prominent players in this local subculture now stand extraordinarily endangered.

|

The beginning of a trend

The city of Boston, which currently designates more than $250,000 a year for graffiti removal, has endured kaleidoscopic waves of vandalism since the 1980s. But Salem — where in 2007 police established a Community Impact Unit specifically (though not exclusively) to investigate and arrest vandals — didn’t see its disproportionately heavy graf scene explode until the mid ’90s.

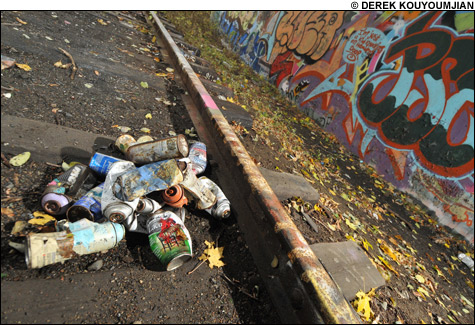

Some date the North Shore epidemic to 1995, when members of the then-young graffiti crew FLOE (Famous Like Old English) convinced operators of the Clemenzi Industrial Park to allow them and other artists to legally utilize the facility’s 500-foot wall facing the Beverly commuter-rail tracks for its art. The area was already under routine attack by FLOE, and its members promised to limit its work to that space in exchange for amnesty.

Willing to cooperate, Clemenzi management agreed, and “The Wall” — or “The Beverly Wall,” as it’s called in graf circles — made its debut. According to one writer (as graffiti artists often refer to themselves and one another), who was partly responsible for securing the space and luring artists from around the world to paint there, “The Beverly Wall created a whole new microcosm of the scene on the North Shore, whereas the South Shore and Boston already had scenes. There wasn’t really much out here before that, but once we got The Wall, people started coming from as close as Connecticut and as far away as Europe.”