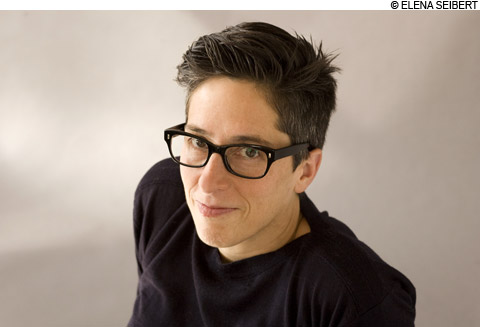

MOTHER LOVE Bechdel's latest book concerns not only her mother, but also a life history of the pioneering child psychiatrist Donald Winnicott, a close reading of Virginia Woolf, and Bechdel's own long foray into psychoanalysis.

|

For years, I faithfully followed Alison Bechdel's comic strip Dykes To Watch Out For, an ongoing lesbian soap opera with a huge cast of characters, all of them vivid and realized. I watched them argue about politics, have affairs, fall in love and split up, mourn, give birth, raise children. I'd know these people if I ran into them on the street: Bechdel's great strength as an artist is a certain mastery of posture and gesture that makes her pen-and-ink figures instantly recognizable as full-fledged human beings.

Later, Bechdel quit the field of comic strips to work on a graphic memoir about her father, a schoolteacher/undertaker whose closeted sexuality and probable suicide (he was run down by a Sunbeam Bread truck; the family assumption is that he stepped deliberately into its path) left an indelible mark on her life and work. Fun Home was hugely and rightfully acclaimed, and Bechdel's follow-up, Are You My Mother? (due from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in May) has been eagerly anticipated.

But I found it hard to enjoy. Are You My Mother? is, of course, the bookend to Fun Home, dealing with Bechdel's distant and difficult mother. This material is less obviously dramatic than Fun Home's; Bechdel mère having indulged in neither an illicit love life nor a grand gesture of self-destruction. She's just a woman with a lot of baggage, all of it interior.

But the book is also preoccupied with other matters: a life history of the pioneering child psychiatrist Donald Winnicott; a close reading of Virginia Woolf's letters and her novel To the Lighthouse; Bechdel's own long foray into psychoanalysis, which has lasted, she writes, "nearly my entire adult life."

In fact, to say the book is a psychoanalytic memoir is an understatement. Chapters have titles like "True and False Self" and "Transitional Objects," and the constant narration is typified by sentences like, "Indeed, my foremost difficulty is the extent to which I have internalized my mother's critical faculties." You can't go two words without tripping over a multisyllabic Latinate.Whenever Bechdel quotes from a text— which is often — she actually draws the page of the book she's quoting, filling her panels with carefully reproduced typeface, with the pertinent quotation highlighted. Floating overhead is her own caption, usually something along the lines of "Compliance is Winnicott's bête noir, spontaneity his summum bonum."

The effect is frustrating; it's like looking at the world through the eyes of an observer who refuses to observe. You long to rip the book out of her hands and force her to gaze upon whatever scene the page must be obscuring. What's on the other side of that hardback? What aren't we seeing? It's as if Bechdel is holding her own story at arm's length. Fun Home was also awash in literary references, but here it's become the primary reading experience.

Bechdel, of course, is hyper-aware of her own tendency to deflect painful experience by intellectualizing it. ". . . For both my mother and me, it's by writing . . . by stepping back a bit from the real thing to look at it, that we are most present," she writes. And later: ". . . [W]oe betide the person with the 'double abnormality' of a False Self and a 'fine intellect' that they can use to escape their pain."

This self-awareness makes it hard to criticize Are You My Mother? — Bechdel seems to have already covered the bases. "It's a . . . a meta-book!" her mother pronounces in the final pages, when Bechdel shows her the manuscript of the book we're reading. Yes, yes, it is. Still, at the end of the book, I don't feel as though I know much about Bechdel's mother, or her girlfriends, or even her therapists. In fact, the most memorable and vivid character is Winnicott, the child psychiatrist, who is drawn with more motion and humanity than practically anyone else in the book. And none of them have the liveliness of the wholly fictional characters that Bechdel drew so well for so long. Maybe Bechdel, having "destroyed" both of her parents, as she says, in print, is overdue for an excursion into fiction. At the very least, something without quotations.

ARE YOU MY MOTHER? | BY ALISON BECHDEL | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT | 304 PAGE | $22

Alison Bechdel | Brattle Theatre, 40 Brattle St, Cambridge | May 2 | 6 pm | 617.661.1515 or harvard.com