LET’S GET LOST: Was it in Chet Baker’s style to jump out a window?

|

In February 1988, I took a break from the Berlin International Film Festival to hear the Chet Baker Quartet playing in a local club. The leather-skinned, hard-living trumpeter had his chops that night, but the cave-like basement club was in a fog from German cigarette smoke. Choking, I ankled before the second set.

I should have stayed on: several months later, on May 13, the 58-year-old Baker jumped, fell, or was pushed from a window in Amsterdam, landing dead on the sidewalk below. He had been active, playing jazz until the end but also appearing on camera in a documentary biography, Let’s Get Lost, that was made by Calvin-Klein-fashion-photographer-turned-filmmaker Bruce Weber. The posthumously released film was a smash, winning the Critics Prize at the 1988 Venice Film Festival. Twenty years later, Let’s Get Lost is getting a deserved second act, with a restored 35mm print screening at the Brattle Theatre January 25 through February 7.

I talked to Weber, a genial, roly-poly man wearing a Gypsy bandana, at the 1988 Toronto International Film Festival, where he showed up with his cameraman, Jeff Preiss, and an entourage of quasi-actors from the surreal, fictional interludes of Let’s Get Lost. What was missing was Baker, four months gone. Did Weber have a theory about his protagonist’s Dutch demise?

“It’s typical of Chet to leave in this cloudy situation,” Weber said. “But it wasn’t really Chet’s style to jump. He was always getting into trouble with drug dealers. He called me in the editing room a month and a half before his death and said, ‘This cocaine dealer is after me.’ But I don’t know, because Chet was always hallucinating. People always ask me about the drugs. Chet took drugs to be normal. He was a rugged Oklahoma boy, and he had a great tolerance for them.”

Baker spent much time before Weber’s camera — blowing trumpet, singing, doing woozy soliloquies — in an unmistakably drug-induced state. When Let’s Get Lost came out, some journalists accused Weber of exploitation, of using Baker’s deteriorated mind and body to his own voyeuristic advantage.

“I don’t think it was a sadistic situation,” is the filmmaker’s version. “I have a responsibility to the person I’m making a film about, when he trusts you. Chet was proud of his knowledge of drugs. He once said he would not change the way he did things. I never felt that Chet was pathetic. He was very aware even in his worst state, without socks in the middle of winter.”

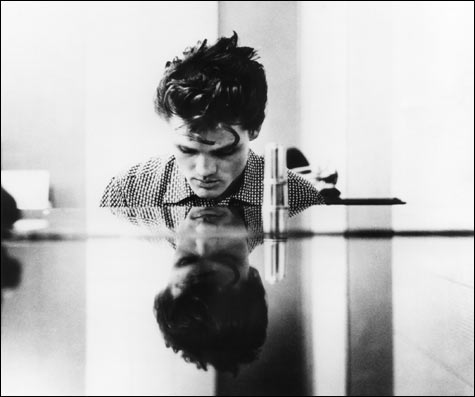

The Baker of Let’s Get Lost, after decades of hard drugs, is wrinkled, toothless, cadaverous. Also, on the eve of his death, hauntingly photogenic. “I think sometimes he looked beautiful so ravaged,” Weber told me. “He had a Dorian Gray thing. One time, he looked like he’d crawled out from under a rock. We’d have to comb his hair. The next time, he’d take three hours to get ready. Even when he was really stoned, Chet would get you into his rhythm. He had a tendency to be very vague, but gradually he got less vague.

“He acted like he didn’t care, but he did. He’d always show up. At Cannes last year, he’d say, ‘I have this film coming out,’ and then get the title wrong.”

Baker flew from that window several months before Let’s Get Lost premiered at Venice. “Couples at the screening were necking,” Weber said. “Chet would have liked that. A real compliment.”

I asked Weber to imagine Baker resurrected at Toronto to trumpet in the first North American screening. The filmmaker smiled. “It would all be craziness. He’d flirt with the girls, leave the table and not return for hours, maybe borrow someone’s jacket. In a day in the life of Chet Baker, nothing was normal.”